The military camps that harboured a deadly enemy

The Corona Pandemic of 2020 feels like it came out of the blue, an invisible enemy which sneaked up on us and made us all keep our distance… a new phenomenon perhaps….? Well this is not the case; a pandemic has hit our shores before and no doubt will again… The last major pandemic occurred when the country was on its knees recovering from the massive death toll and destruction of the First World War.

The forgotten pandemic

1918 was the year of peace after the First World War, yet an unimaginable year of suffering and death from an Influenza pandemic lay ahead. A virus would rip across nations wiping out 50 – 100 million lives worldwide. Even with its terrifying death toll, the 1918 flu pandemic has somehow been eclipsed from the history books by The Great War itself and maybe due to a desire to focus on the victory over our physical enemy rather than a global population succumbing to an infectious, microscopic one. Whatever the reason, the pandemic of 2020 has brought the 1918 outbreak back into focus.

The influenza pandemic of 1918 – 1919 killed 250,000 people in Britain and killed more people globally than both World Wars put together, It was a particular strain of the Flu which was unusual in that it caused most deaths in adults aged 20 to 40, the inverse of most flu seasons when deaths fall most heavily on the elderly and infants. It was an incomprehensible blow to a recovering nation that had seen masses of its young men mown down by German guns.

‘Spanish’ Flu?

“I had a little bird, Its name was Enza. I opened the window, And in-flu-enza”

The pandemic was misleadingly named ‘The Spanish Influenza’, a name which originated because in the early months of the pandemic, wartime censorship in the UK, USA and Germany minimised reports on the seriousness of the outbreak in order to boost morale and prevent panic. However, detailed reports were emerging from neutral Spain, where King Alfonso XIII fell gravely ill to the virus, giving rise to the nickname ‘Spanish flu’. But the actual origin of this new strain of influenza was thought to be a farm in Kansas USA, where an avian or swine flu strain transferred from animal to human.

This strain of influenza then mutated over time and adapted to human to human contact which raged through the population. It came in three waves (Spring 1918, Autumn 1918, and Winter 1919) and the second wave was unusually deadly.

Many researchers have suggested that the conditions of the war significantly aided the spread of the disease and others have argued that the course of the war was influenced by the pandemic.

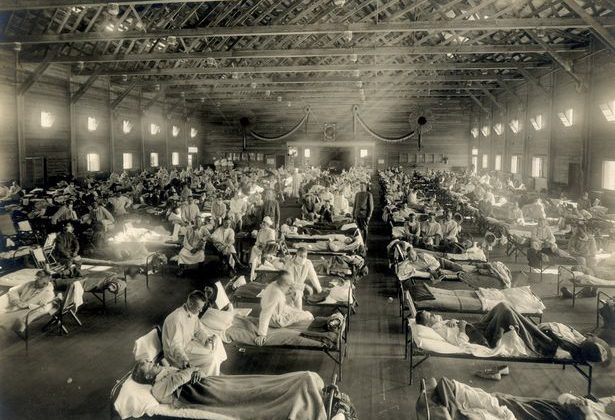

The first wave was identified in Kansas and in military camps across America, but at this time little acknowledgment was given to the growing cases and few noticed the epidemic amongst the troops during the war. This lack of action was later criticised when the numbers of soldiers falling victim to the illness could not be ignored during the winter of 1918.

The virus thrived on the war conditions of men tightly packed into trenches and was carried home with the returning soldiers travelling to busy ports like Boston for medical leave. The high-level of transport between the U.S. and Europe allowed the virus to spread globally. Soldiers with mild strains of the virus were left in the trenches and those with severe illness were sent home, infecting anyone they encountered along the way due to the highly contagious nature of the disease.

As well as passing from soldier to soldier the virus was spreading virulently through the civilian population who were working hard in busy factories to support the war effort. And in November 1918, as people came together to celebrate the end of the war, the infectious enemy ran rampant through jubilant crowds and parades.

They survived the trenches, only to succumb to an invisible virus

The soldiers who were lucky enough to make it out of the war alive, returned home only to fall ill to this unknown virus. Many succumbed as their weakened bodies were so battered by the years of battle they had endured.

The virus had mutated over the course of the year and became more deadly to the already weakened bodies and immune systems of war-torn soldiers, and now all age groups were falling ill and dying. The emergency was soon unavoidable as returning soldiers in overrun medical compounds presenting symptoms which could no longer be explained as exhaustion and war fatigue.

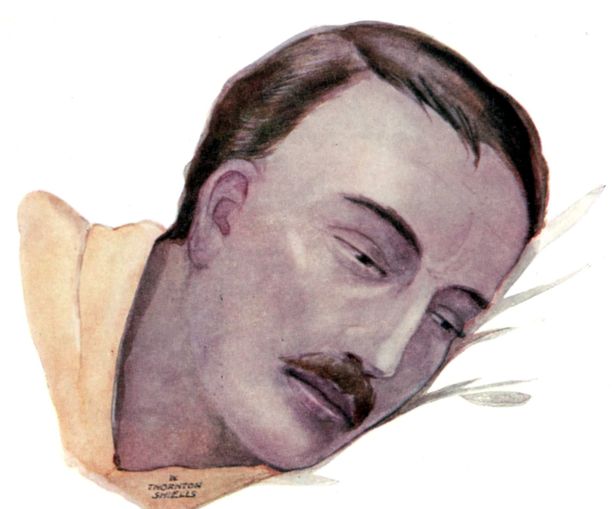

The patients were all displaying common symptoms of cyanosis, a distinctive purple-blue discolouration of the lips, ears and cheeks, caused by the loss of oxygen to the heart, a characteristic of pneumonia.

In the South West of England, one of the bitter tragedies is that the armistice celebrations of Bristolians on November 11th, 1918 helped to spread the deadly disease and caused deaths to peak across the region.

In Paignton Devon, over 100 American servicemen died in a fortnight at the Oldway War Hospital where they had come to convalesce at the end of the War. There were so many deaths that they were buried in a communal grave in Paignton Cemetery. And on a war memorial in Torquay, New Zealand servicemen are commemorated who died after also coming to the the West Country to recuperate.

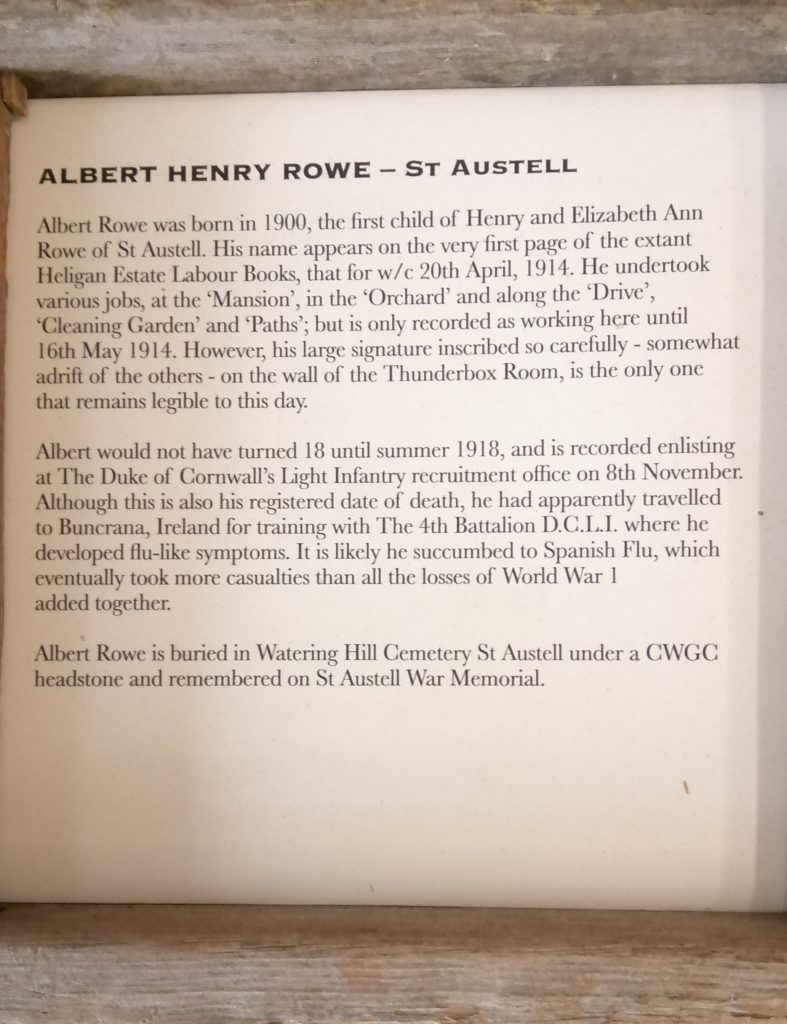

In Cornwall, the Heligan Estate records an employee Albert Rowe, who enlisted with the DCLI (Duke of Cornwall’s Light Infantry) at Bodmin Keep, only to fall ill with the fatal Influenza and die on the very same day.

A receptive response to public health initiatives

In many countries local authorities imposed curfews and banned public gatherings, and just as we’ve seen in 2020, these included restrictions to funerals, weddings and the closure of schools, churches and theatres. People were advised to avoid shaking hands and to stay indoors, libraries put a halt on lending books and a ‘Sanitary Code’ was put in place banning spitting.

Because of the war years, citizens were familiar with national measures, propaganda campaigns and restrictions. So, nationalism and a sense of civic duty for public health pervaded, and people followed the restrictions asked of them by the government to slow the spread of the disease.

The war had also shone a spotlight on scientific and medical advances in germ theory and the development of antiseptic surgery, in treating battle wounds and sick soldiers. These new theories and practices for prevention, diagnostics and treatment were readily applied to the influenza patients.

By the summer of 1919, the flu pandemic came to an end, and a resilient global community re-built itself once again. But the lack of readiness and suitable healthcare for a nation on its knees triggered a concern about public health that would lead to the emergence of a National Health Service (NHS) some 30 years later.