Lap Crafts for the convalescing soldier

During World War One, injured soldiers were sent to hospitals to recover from their injuries, which could include amputations, blindness and ‘shell shock’. The hospitals aimed to be clean, quiet environments where soldiers could carry out calm, meditative work. These activities included embroidery (or ‘fancy work’) as well as beadwork and woodworking and was an early example of occupational therapy.

Occupational therapy is the idea that working can be physically and psychologically beneficial for trauma patients. Although Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) did not exist as a diagnosis yet, soldiers were returning home with ‘shell shock’ that needed treatment. ‘Lap crafts’ were good for fine motor skills, so appropriate for men with limb injuries as well as the painful ticks of shell shock, as they could do it in bed.

Handcrafted by Soldiers

Embroidery pieces made by soldiers were often heraldic and patriotic, for instance showing the soldier’s regimental badge, as well as where they were fighting and the date. The Red Cross provided printed embroidery templates with patriotic messages, which helped beginners to learn.

Another beautiful example is this geometric necklace in green and silver beads, finished with a decorative tassel. It was made by Private Walter John Cressey from the Middlesex Regiment as he recovered at the Queen Alexandra Military Hospital, London. Cressey had lost his sight and four fingers from a gas attack, and yet made this remarkable jewellery.

A famous example of collaborative WW1 embroidery is the altar cloth at St Paul’s Cathedral, which is 10 feet wide and covered in intricate floral patterns. It was organised by women from the Royal School of Needlework and involved 133 soldiers from different countries, and used at a national service of thanksgiving in 1919. Until recently it was thought that the cloth had been destroyed during the Blitz, but it was kept safe and has been restored for a display commemorating 100 years since WW1.

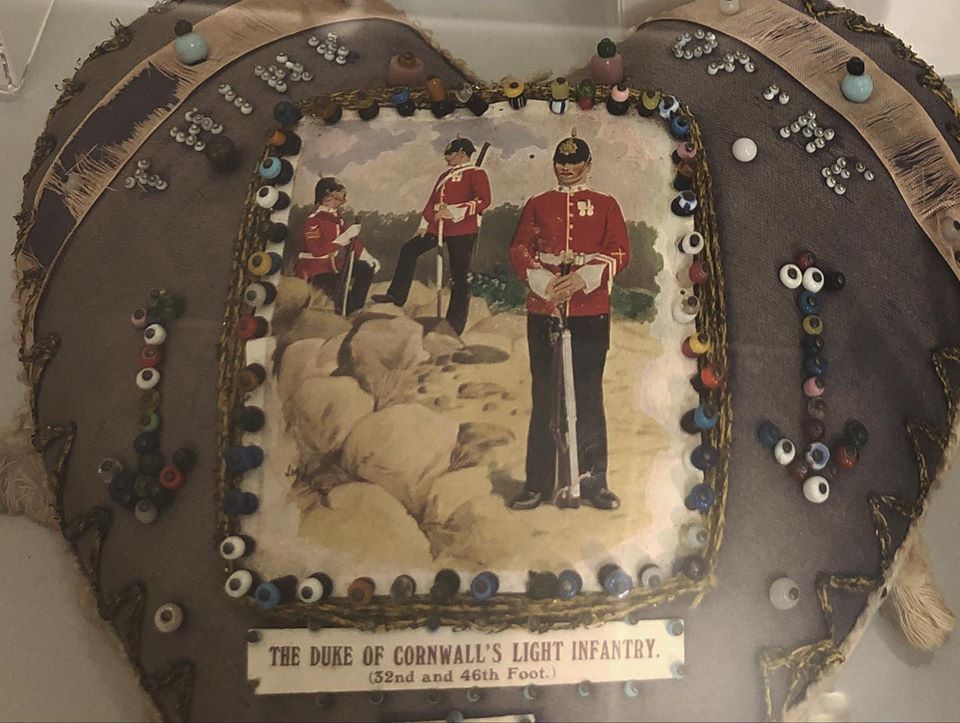

In our museum, one of our best examples is this sweetheart pincushion. The hearts were created using kits which contained the fabric, beads and pins needed for the soldiers to use. They were usually personalised to an individual e.g. for their ‘sweetheart’ or loved ones, or to reflect their regiment. For instance soldiers might decorate their cushion with the regimental insignia, poems or messages printed on small silk patches that came in cigarette packages with rations.

You can see a 3D scan of the pin cushion here.

Rehabilitation

Since WW1, occupational therapy has proved to be very helpful, having a positive effect on patients health and well-being, often by creating structure and organising time. Out of medical environments, studies find that spending time on creative goals during the day is associated with positive mental effects (Conner, DeYoung and Silvia 2018).

Embroidery was successful for rehabilitation as it is a small, flat, quiet, intimate activity that can be done in a group or alone. It would add focus and purpose to recovery, improve manual dexterity, prevent boredom and melancholy. It also created economic opportunities, as the embroidery and other ornaments could be sold at the hospital shops to raise money.

Where are the women?

It’s interesting to examine embroidery as a therapy for soldiers, as it is so often gendered as a ‘feminine’ activity. Clearly there is no reason to limit sewing to any group of people. An issue with these objects is that we often know the names of the men who created them, but rarely who taught them. For instance the altar cloth at St Paul’s was pieced together by women, who also volunteered to teach the soldiers, and yet we don’t know who they were.

One teacher we do know is Lousia Pesel, who was the head of the Winchester Cathedral Broderers, organising over 180 volunteers to create 98 cushions and 300 kneelers for the church. During WW1, Pesel worked with Belgian refugees in Bradford as well as soldiers, teaching them to sew ‘for the soothing value of doing something with their hands’. Her work was so successful that the scheme was copied in other towns. She also collected textiles to study techniques, which were displayed in the exhibition ‘Unbound: Visionary Women Collecting Textiles’ at Two Temple Palace, London. She also worked for the Victoria and Albert Museum and wrote books such as ‘English Embroidery’ as she wanted to record textile history.

Health & Wellbeing

These objects show us the amazing power of craft in physical and mental healing. The embroidery at Bodmin Keep especially shows us the pride our soldiers had in their regiment.

“How brilliant to construct something as a means of healing from so much destruction – to stitch, string, mould, weave, paint, paste, and knit in order to put things together again after such a painful time in history” (Den Hartog 2018)

Sources

Brayshaw, E. (2017) Stitching lives back together: men’s rehabilitation embroidery in WW1. Available at: http://theconversation.com/stitching-lives-back-together-mens-rehabilitation-embroidery-in-wwi-76326 (Accessed: 2nd April 2020).

Chevalier, T. (2020) Tracy Chevalier on the unsung heroine of British textiles who taught shell-shocked soldiers how to sew. Available at: https://www.telegraph.co.uk/art/artists/tracy-chevalier-unsung-heroine-british-textiles-taught-shell/ (Accessed: 9 April 2020).

Clayton, E. (2019) Bradford seamstress’s sewing therapy for shellshocked WW1 soldiers. Available at: https://www.thetelegraphandargus.co.uk/news/17898864.bradford-seamstress-39-s-sewing-therapy-shellshocked-ww1-soldiers/ (Accessed: 9 April 2020).

Conner, T. S.; DeYoung, C. G.

and Silvia, P. J. (2018) ‘Everyday creative activity as a path to flourishing’,

Journal of Positive Psychology, 13(2), pp. 181-189.

Cumbria’s Museum of Military Life (no date) Sewing on the Front Line. Available at: https://www.cumbriasmuseumofmilitarylife.org/whats-on/burma-exhibition/a-stitch-in-time/

(Available at: 9 April 2020).

Daigle, T. (2018) Beauty out of pain: Canadian soldiers’ embroidery was therapy for the scars of war. Available at: https://www.cbc.ca/news/world/first-world-war-soldiers-altar-cloth-embroidery-1.4895370 (Accessed: 3rd April 2020).

Den Hartog, K. (2018) The Power of Craft: Occupational Therapy in WW1. Available at: https://thecowkeeperswish.com/2018/09/06/the-power-of-craft-occupational-therapy-in-ww1/ (Accessed: 6 April 2020).

Imperial War Museum (no date) Necklace, beadwork, handmade. Available at: https://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/30084232 (Accessed: 6 April 2020).

Inspirations (2018) Embroidery as Rehabilitation after WW1. Available at: https://www.inspirationsstudios.com/embroidery-as-rehabilitation-after-wwi/ (Accessed: 3 April 2020).

The History Blog (2014) Altar cloth stitched by injured soldiers during WW1 to go on display. Available at: http://www.thehistoryblog.com/archives/29681 (Accessed: 6 April 2020).

Sources:

Townsend, E. A. and Polatajko, H. J. (2007). Enabling Occupation II: Advancing an Occupational Therapy Vision for Health, Well-being, & Justice Through Occupation. Canadian Association of Occupational Therapists.