In my last blog post I introduced a game called ‘From the Ranks to Field Marshal’. If you missed it, you can read it by clicking here. Now, that we have a good grasp of the rules, let’s look at why the game was created and who would have played it.

Board games for boredom

Humans have played board games for thousands of years all across the world. The ancient Greeks, Romans, and Aztecs all had games that would bring people together and overcome boredom. Board games could also be used to plan attacks by mapping out the battlefield and assessing different courses of action. Some of the earliest known board games come from Iran and Egypt and date to around 3000-2000 BC.

Jumping to the 1900s, the developments in mass production helped to make board games cheaper and more accessible. They remained popular pastimes for bringing families and friends together, and for keeping children occupied.

During wartime, games were an important form of entertainment for the soldiers fighting on the front and for those in recovery.

German board game produced in the early 1900s. © Stadtmuseum Berlin

In the First World War, a board game known as ‘Don’t Get Annoyed With Me’ (Mensch Aergere Dich Nicht) was popular with German soldiers. The aim of this game was to get your counters to the ‘home’ area first. You could sabotage other players by knocking off their pieces from the board.

I suspect that our donated board game – From the Ranks to Field Marshal – was not aimed at soldiers. The game makes light of military life; it simplifies the promotion process and ignores the seriousness of typhoid, of being taken prisoner, or of facing a court martialling. Would such a game really be popular with the soldiers experiencing the harsh realities of fighting at the front?

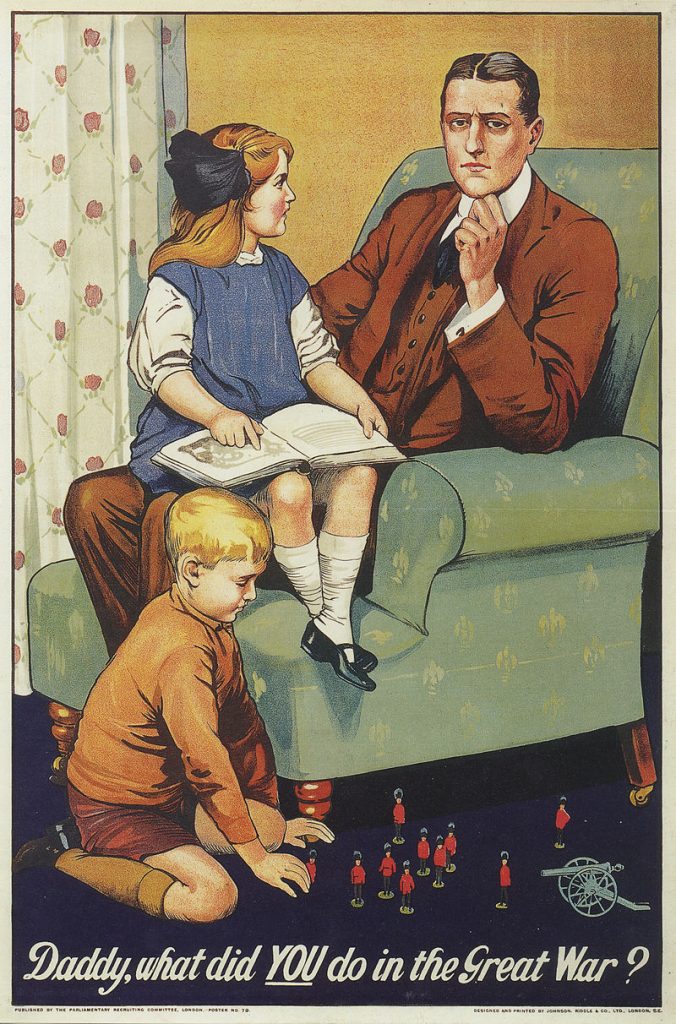

Instead, I think the game targeted children and their families, inviting them into the military world. It was a clever form of wartime propaganda that stemmed from the popular support for war in 1914.

War Fervour and Propaganda

Britain’s decision to enter the war on 4th August 1914 was a cautious one. The government wanted to avoid anti-war protests and they were concerned that public opinion would turn against them. Indeed, in the days leading up to the announcement, thousands of people had gathered in Trafalgar Square in London to protest Britain joining the conflict on mainland Europe.

Yet, the vast majority of the British public responded with excitement to the declaration of war. On the evening of 4th August, thousands celebrated outside of Buckingham Palace, singing the national anthem. Hundreds of thousands of men readily sign up to serve in the early years; it was not until 1916 that conscription was introduced. This war fervour was born out of national pride: Britain was about to make a powerful and heroic contribution to the war. We were going to protect Europe from the growing, tyrannical power centred in Germany.

Making a nation

When war broke out, British manufacturers joined in with the patriotic celebrations. Their war-themed goods would be popular with the largely pro-war public, resulting in more sales and money. This type of production was also likely to reflect the manufacturers’ personal pro-war views.

For the government, the pro-British production was key for generating support especially given the war’s growing human and financial costs. These goods would help reinforce the censored information being fed to the British public, giving them the impression that the war was going successfully. The government also encouraged the injured soldiers discharged from service to find employment, including in toy and doll making factories.

The result was an unprecedented production of military themed children’s games and toys. A range of figurines were created depicting soldiers, aircraft, ships, and cannons. Army bears, dolls, books, and journals were also produced alongside board games.

Good games and good wars

Every country had a similar production system that celebrated their war efforts and played upon the stereotypes of different nationalities. In making it into a game, the war became more palatable and saleable for those at home.

Being able to produce toys during wartime was also a way to convince the public – as well as other nations – that your prosperity was not being drained. The need for positive messaging is part of the reason why the War Propaganda Bureau, and later the Department of Information, subsidised the production of children’s books and toys in Britain.

In their images and descriptions, these military games could be fairly violent, but the realities of war were not really communicated. Instead, by presenting the war as a ‘good war’, so too could the deaths of serving male relatives be marketed as ‘good deaths’.

So, what impact did these ‘good war’ games and toys have on children?

It takes an army to raise a child!

Children learn from everything and everyone around them and these early experiences have a big impact upon our later lives. Games and toys help us develop important life skills such as communication, concentration, decision-making, and knowing how to follow rules. Our board game, From the Ranks to Field Marshal, would have been part of this ‘unofficial’ learning process for children in the early war period.

As I described earlier, From the Ranks to Field Marshal would teach children about the structure of the army and how to progress through the ranks. Naturally, it downplays the threats involved in military life in order to generate excitement over the idea of military service.

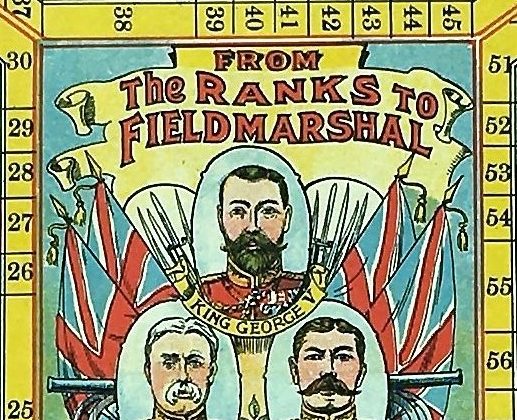

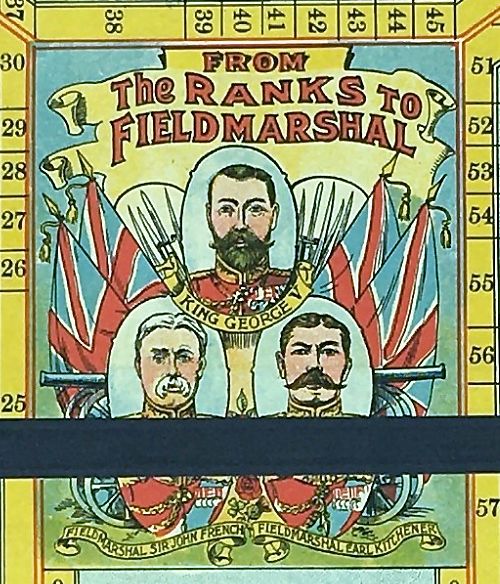

By playing this game, children would begin to see the military as a common part of everyday life. They would become familiar with some of the key authority figures in the British Expeditionary Force (BEF). George V, Sir John French, and Earl Kitchener are three Field Marshals of the First World War depicted in the centre of the board.

Note: the image of Sir John French tells us that this board game was produced before 10th December 1915. On this date, John French was removed as the Commander of the British Expeditionary Forces and was replaced by General Douglas Haig.

Playing this game would build upon the general war fervour and the impact of seeing so many men – their dads, older brothers and friends, uncles, cousins – enlist as soldiers. It gave the children their own way to connect to the war and perhaps helped them feel closer to their missing relatives.

Children’s war effort

Pro-war propaganda, like this board game, was effective in getting children to contribute to the war effort. Like the women and the remaining men, children were needed to fill the void of industrial manpower. They became more involved in collecting harvests and looking after allotments. They joined the Scouts and Guides to help during air raids and to prepare resources to send to the front. Some would even donate their pocket money to help with the war effort.

Post-war period

Over time, the production of military games and toys decreased as more resources had to be directed towards military production for the front. The effectiveness of war memorabilia likely declined as well because people became disillusioned. They wanted the war to be over quickly, and did not expect it to last for four years.

After the war, military board games and toys may have been donated, re-sold, or thrown away. The majority likely remained in family homes. But, how enjoyable would these reminders of war have been, when the realities of fighting on the front became known?

Written by Isabella Hogan, Trainee Curator at Bodmin Keep