How do we create, collect and display objects to remember our history? What can souvenirs and war trophies tell us about the experiences of the Duke of Cornwall’s Light Infantry (DCLI) and Light Infantry (LI) regiments deployed abroad? This exhibition explores three different types of objects which hold memories:

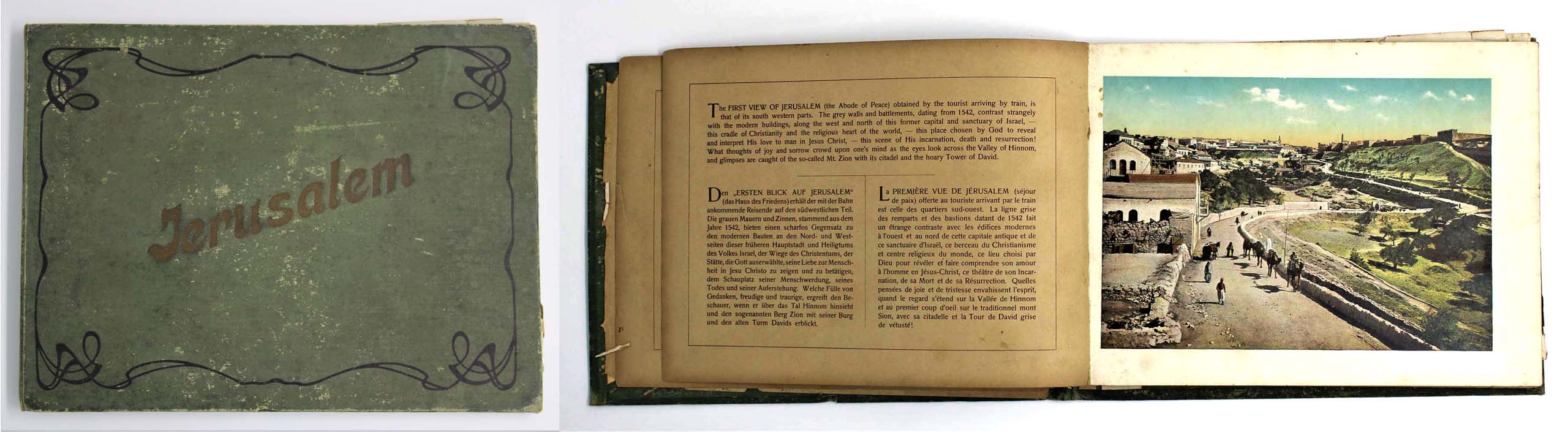

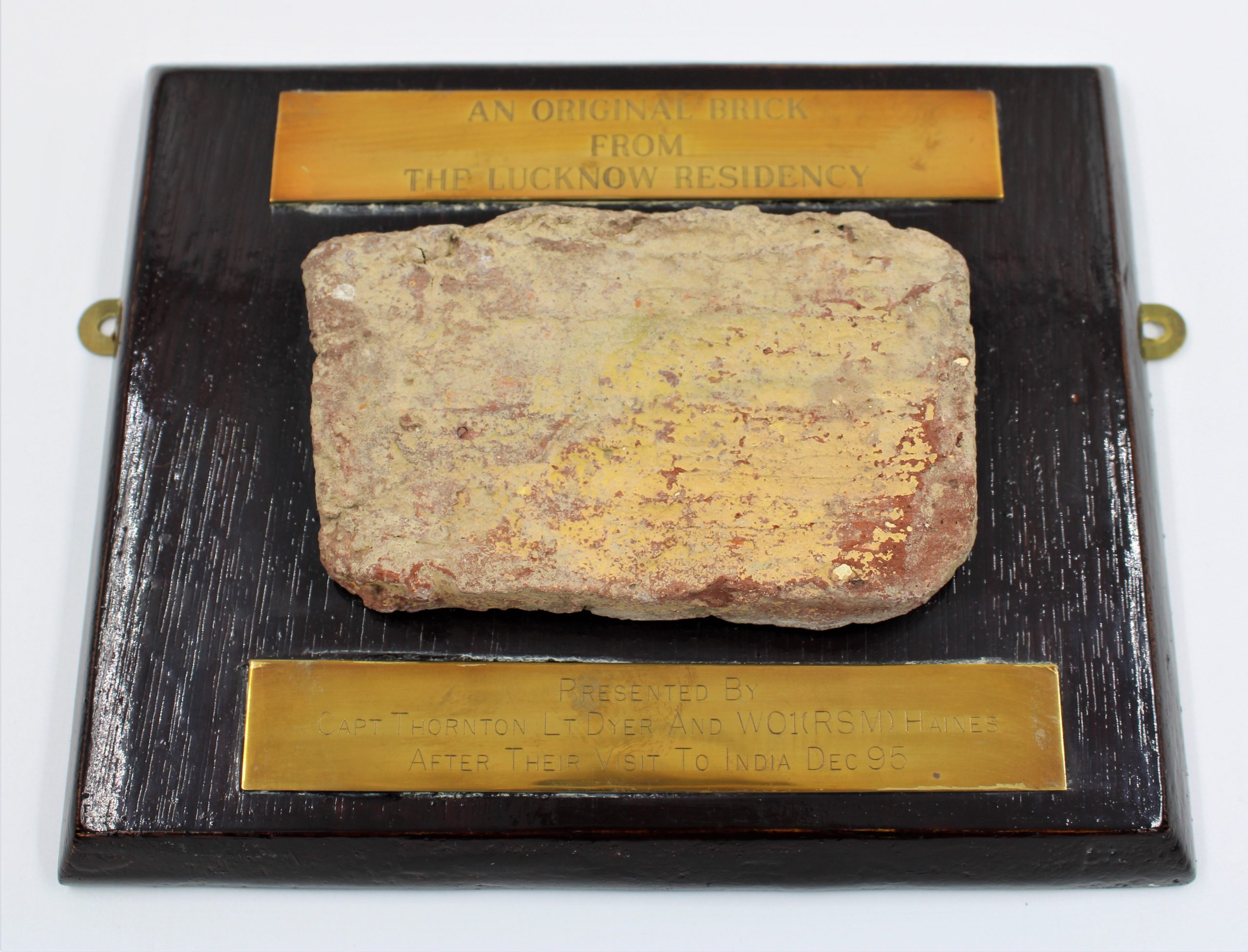

Souvenirs – Objects collected by soldiers to remember places where they have served.

Commemorative objects – Objects specifically made to memorialise a campaign or battle experience.

War trophies – Objects taken, sometimes by force, and displayed by the regiment to represent a victory. These are also known as ‘spoils of war’.

Objects collected during conflict can be memorials of violent or traumatic events. Some commemorate the strength and resilience of individuals. Others are reminders of the resourcefulness and creativity of people during times of hardship. The souvenirs and spoils that soldiers have chosen to bring home play an important role in how we remember some of the most challenging moments of history.