Celebrating the inspirational life of local woman Emily Hobhouse

Emily Hobhouse was a spirited Cornish woman, who made her name as a welfare campaigner during the Boer war and continued her campaigning throughout World War One.

She was born close to Bodmin, in the rectory at St Ive near Liskeard, on the 9th April, 1860. Her father Reginald was the rector and her mother Caroline was the daughter of Sir William Salusbury-Trelawny, one of the oldest and richest families in Cornwall.

Her mother died young and Emily devoted her early adulthood to dutifully caring for her father. It was not until his death in 1895 that she was able to realise her life’s ambition as a Christian missionary.

Cornish Copper Miners

At 38 years old, she travelled to Virginia, USA to improve the working conditions of Cornish copper miners who had emigrated there after the slump of the 1880s. Her former rectory life had ill-prepared her for this, and the 3,000 strong male community with saloons and brothels was quite the eye opener I’m sure. But nevertheless, with her immense courage and tenacity, she gradually gained the friendship and respect of this male- dominated and rather rough community.

When she came back to England 3 years later, she was interested in being involved in the Women’s suffragette movement. She later became chair of the People’s Suffrage Federation which passionately protested for women’s right to the vote.

Second Boer War

Emily Hobhouse is best known and revered for her strong-minded determination to expose the appalling conditions of Boer families, who were herded into concentration camps run by the British during the Second Boer War in South Africa.

The Second Boer war lasted from 1899 to 1902 and was fought between the British Empire and two Boer states; The South African Republic and The Orange Free State, over the Empire’s influence in South Africa.

Hobhouse was invited to become the secretary of the women’s branch of the South African Conciliation Committee. When she heard reports of the mistreatment of Boer people by the British Military, she quickly founded the Distress Fund for South African Women and Children to raise funds for their relief.

In December, she set sail to South Africa to distribute the funds and to investigate the inhumane conditions Boer families were forced to live in.

When Hobhouse left England, she only knew about one concentration camp existing, but on arrival she discovered there were many more. She was horrified by the overcrowding, neglect and lack of resources of the camps, which were full of undernourished children and with disease rampant.

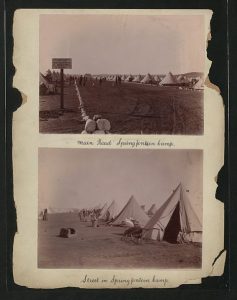

During the later part of the South African war, a ‘scorched earth policy’ was adopted by Field Marshal Lord Roberts (and continued by his successor General Lord Kitchener). With the aim of starving the Boer army into submission, every Boer farm was burnt and all crops, livestock and food stores destroyed. The thousands of woman, children and elderly men who had lived on these farms were forcibly transported to tented camps many miles from their homes.

The scheme was not properly thought through, and it quickly became obvious that the available administrative capacity of the army was totally inadequate for this operation. The results were appalling; food supplies were meagre at the best of times, and often non-existent and there was a lack of clean drinking water. The inadequate shelter, poor diet, bad hygiene and overcrowding led to malnutrition and endemic contagious diseases such as measles, typhoid and dysentery to which the children were particularly vulnerable. Coupled with a shortage of modern medical facilities, over 26,000 women and children perished in these concentration camps.

There is no evidence to support the theory that the British deliberately set out to destroy the Boer race. The tragic disaster was caused by the stupidity and inefficiency of those trusted to run the camps and by the failure of the commander- in-chief to take any steps to remedy the situation.

Eventually, there were a total of 45 tented camps built for Boer internees and 64 for black Africans. Of the 28,000 Boer men captured as prisoners of war, 25,630 were separated from their families and sent overseas to camps in Sri Lanka, India, Portugal and The Caribbean.

The British ultimately overpowered the Boers, and at the end of the war in 1902 all detainees of the concentration camps were freed. However, the Boers had to swear allegiance to the crown; those who didn’t were not allowed to return to South Africa.

Emily Hobhouse was instrumental in bringing relief to the concentration camps, managing to increase the amount of soap, tents, beds and clean drinking water within them, as well as raising public awareness in Europe of the atrocities. Although when she returned to England she was largely criticised by the British government and referred to as “That bloody woman!” they were completely unsympathetic about the camp conditions and she was banned from returning to South Africa! But her tenacity and dogged personality came through again, as she refused to go away and sent a stream of letters to newspapers, so that the camps became an international scandal.

In 1903 she was able to go back to South Africa, where she led a rehabilitation project; a scheme where Boer women were taught valuable skills of lace-making, spinning and weaving, to enable them to rebuild their lives.

Word War One

In later life Emily continued her activism by showing her strong opposition to the First World War. She was the only British civilian travel to Germany in the middle of the war to talk to the German Foreign Minister to find a way to negotiate peace and end the war. She also organised the writing, signing and publishing in January 1915 of the “Open Christmas Letter”, addressed “To the Women of Germany and Austria”.

The Open Christmas Letter was a public message for peace signed by a group of 101 British suffragists at the end of 1914. As the first Christmas of the war approached, it was a direct response to letters written to American feminist Carrie Chapman Catt, the president of the International Woman Suffrage Alliance (IWSA), by a small group of German women’s rights activists. Published in January 1915 in Jus Suffragii, the journal of the IWSA, the Open Christmas Letter was answered two months later by a group of 155 prominent German and Austrian women who were pacifists.

The exchange of letters between women of nations at war helped promote the aims of peace and helped to prevent the fracturing of the unity which lay in the common goal they shared – suffrage for women.

Her Legacy

Emily Hobhouse died on 8th June 1926. Her funeral went unreported, even by the local newspaper and her name in England was quickly forgotten. By contrast however, a ceremony took place in Bloemfontein on 27th October 1926, in which her ashes (which had been taken out to South Africa) were laid to rest at the imposing ‘National Woman’s Monument’ built to the commemorate the suffering of 26,000 Boer Women and children.

Tens of thousands of mourners both black and white attended the ceremony – the greatest farewell ever accorded to a non-South African.

In his oration Jan Smuts said:

“We stood alone in the world, almost friendless among the peoples, the smallest nation ranged against the mightiest empire on earth. And then one small hand, the hand of a woman was stretched out to us. At that darkest hour, when our race almost seemed doomed to extinction, she appeared as an angel, as a heaven-sent messenger. Strangest of all she was an Englishwoman… During those eventful years she gave us all she had; she gave her health and she poured out her soul… It was her wish that her ashes should be buried in this land, should become part and parcel of the land where the best service of her life had been rendered. She now becomes one with us everlasting”.

If you would like to learn more about the Second Boer War and the Prisoners of War we have a permanent display in the museum galleries at Bodmin Keep.