Smart images of men in khaki concealed the reality that kitting out an ever-expanding army involved compromise, resistance and improvisation. In this blog we look at how soldiers have adapted & maintained their uniforms during wartime. From recycling and re-using captured enemy uniforms, ‘Kitchener Blue’ and make do and mending what you have, in war time frugality and sparsity.

British Army uniform in WWI

Battledress was the standard field uniform for soldiers, and it was produced to the ‘utility pattern’ – its design modified over time to make it more efficient to produce.

The British Army of 1914 were the only army to wear any form of camouflage uniform; the value of ‘natural coloured’ clothing was quickly recognised by the British Army, who introduced Khaki drill.

In World War One, a British soldier wore the 1902 Pattern Service Dress tunic and trousers. This was a thick woollen tunic, dyed khaki. There were two breast pockets for personal items and the soldier’s Pay Book, two smaller pockets for other items, and an internal pocket sewn under the right flap of the lower tunic where the first field dressing was kept.

The soldier was issued with the 1908 Pattern Webbing for carrying personal equipment and he was armed with the Short Magazine Lee–Enfield rifle.

A stiffened peak cap was worn, made of the same material, with a leather strap, brass fitting and secured with two small brass buttons. Puttees were worn round the ankles and calves, and ammunition boots with hobnail boots on the feet.

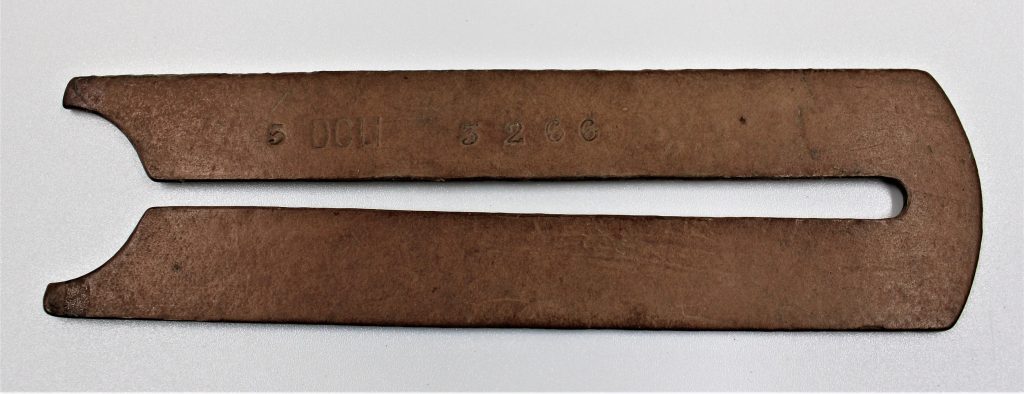

The British were the first European army to replace leather belts and pouches with webbing, a strong material made from woven cotton, which had been pioneered in the United States. The 1908 patten webbing equipment comprised a wide belt, left and right ammunition pouches which held 75 rounds of ammunition each, left and right braces, a bayonet frog (the strap that a bayonet was held with, similar to a gun holster),an attachment for the entrenching tool handle, an entrenching tool head (comprised of a pick and shovel) in web cover, water bottle carrier, small haversack and large pack. A mess tin was worn attached to one of the packs and was contained inside a cloth buff-coloured khaki cover.

Inside the haversack were personal items, and a large pack for carrying the soldier’s Great Coat or a blanket.

On the outbreak of war, it became clear that the Mills Equipment Company in the U.S could not keep up with the sudden demand for webbing. Therefore, a version of the 1908 equipment was designed to be made in leather, as both Britain and the USA had large leather working industries with excess capacity.

The Broadie Helmet

The first delivery of a protective steel helmet – the Broadie Helmet to the British Army was in 1915. Initially there were far from enough helmets to equip every man, so they were designated as “trench stores”, to be kept in the front line and used by each unit that occupied the sector. It was not until the summer of 1916, when the first 1 million helmets had been produced, that they could be generally issued.

The helmet reduced casualties but was criticised by General Plumber (commander of the 2nd Army in the Second World War) on the grounds that it was too shallow, too reflective, its rim was too sharp, and its lining was too slippery. These criticisms were addressed in the Mark I model helmet of 1916 which had a separate folded rim, a two-part liner, and matte khaki paint finished with sand, sawdust, or crushed cork to give a dull, non-reflective appearance.

Rag Tag Army WWI

As Britain prepared for war the army came under extreme pressure to recruit, train, clothe and equip masses of inexperienced men, often struggling to offer them a smooth transition into the army.

Victoria Barracks, in Bodmin, headquarters of the DCLI, held the Quartermaster’s stores, where uniform, mobilisation equipment & weapons were stored. However, from the idealised recruitment images to the coarse trousers and ill-fitting tunics, it soon became clear Britain didn’t have enough kit. The struggle to be able to supply military uniforms to all recruits became apparent and a nationwide problem.

Shortages undermined the optimism of propaganda posters, particularly the powerful images of men in khaki that drove many to recruiting stations in the first place. The manufacture of uniform to supply a mass influx of new recruits was always going to be a massive undertaking, so in the first few weeks some early recruits were forced to wear replacement uniforms, dubbed ‘Kitchener Blue’.

Kitchener blue

Once it became clear that uniform production could not keep up with the supply of soldiers, Kitchener relaxed regulation appearance for the troops. He took the view that the improvised outfits would be adequate in the short term as long as men in individual units dressed alike. The Kitchener Blue ‘uniform’ was obtained from a range of unlikely sources, such as post office stocks and greatcoats purchased from the clothing trade.

With these improvised outfits, the British army looked less like a professional military force, and more like a rag tag army. The War Office ordered vast quantities of jackets, trousers and greatcoats from Canada and the United States to eventually meet demand.

The British were not alone in uniform shortages and ‘making do’ – the Soviets also had problems supplying their troops despite allied help. And Germany had great difficulty with uniform supplies as they had the extra problem of the blockade in both World Wars to contend with.

‘A soldier guarding the Second World War underground tunnels at Porthcurno telegraph station wearing a First World War great coat.’ Photo Courtesy of PK Porthcurno

It’s why it can be misleading in some photographs to simply look at uniform to date the picture, as often Volunteer Troops or Home Guard Troops during WWII would be issued WWI uniform as this image shows.

Thrifty Nazis

It is widely thought that Germans reused captured uniforms and uniform cloth. The quality of British shirts and trousers were appreciated because they withstood the conditions better and did not fade so much. They would make small modifications to the uniforms and caps to make them look more in line with the German issue uniform. Dutch uniform stocks captured in 1940 were handed out to allies in Yugoslavia and all the British Great Coats captured in Norway and Denmark would be re-issued to German soldiers to make up shortages.

They also used Italian uniforms confiscated during the late war period by replacing the tunic buttons, so they had a more German appearance.

Hilfswilliger or ‘Hiwi’s’– (an auxiliary volunteer soldier for the Nazi’s), often wore Russian uniform with an armband. And the blue grey French uniform was reused to make uniforms for the Russian Liberation Army.

The Kriegsmarine (the Navy of Nazi Germany) made use of British Battledress captured in 1940. It was widely issued in U-Boat crews with their own insignia sewn on, they would also re-use British underwear such as socks, boots and gaiters.

Clothes rationing in WWII

During the long campaign of the Second World War and a large proportion of the British population permitted to wear some sort of uniform, the demand for military attire put an enormous strain on the textile and clothing industries in Britain. So, to ensure that the limited resources went towards the war effort; raw materials, manufacturing and labour was ploughed into uniform production. Ultimately creating shortages in the shoe and garment industry so new clothes became expensive and a luxury for the wealthy.

Civilian Clothes Rationing

In Britain during the Second World War the British Government needed to put rules in place to safeguard the raw materials for clothing for war production

On June 1st 1941 The President of the Board of Trade announced clothes rationing to the British public.

Civilians would now need to use their allocated coupons to buy clothing which would limit how many items each person could purchase in a year, thus reducing the overall retail market of civilian clothes enormously.

Women and households were encouraged to ‘Make Do & Mend’ to help win the war. The campaign’s aim was to make clothes last longer. As the war went on coupon limits were severely restricted which made buying new, almost impossible for most people, so repair and resourcefulness was the only option available.

Shortages of new fabrics and material forced imagination and innovative thinking of using old clothes and homemade accessories to smarten up an outfit. Many women would use furnishing fabrics and blackout material. Parachute material was particularly valued for underwear, nightclothes and wedding dresses.

The Utility Clothing Scheme in 1942 was developed out of the need to standardise production to free up more resources for the war effort. Strictly specified utility fabric and clothes were made for civilians with a guarantee of quality and value for money with their money and coupons.

Land girls and lipstick

Although a growing trend in war time was towards a more relaxed and informal style, women were frequently encouraged not to let standards slip too far. It was a genuine concern that a lack in personal appearance could be a sign of low morale which would in turn affect the war effort. So although women enjoyed the newly acquired freedom of wearing trousers and doing manual work to support the war effort, it in turn created a trend for utilitarian coats, trouser suits and zipper-front jumpsuits – life went on between the air raids and the farm work but women still looked in the mirror!

Make up was never rationed but was looked upon as a luxury item and therefore expensive to buy. Some cosmetic firms also switched production methods to support the war effort, so instead of manufacturing face powder they would instead make army foot powder, and perfume factories instead made anti-gas ointment.

Uniform maintenance and up-keep

A soldier’s kit has naturally evolved over the decades of military warfare. Although one thing that has remained constant and something which is sometimes a surprise to people is that soldiers have always been very adept with a needle and thread.

Sewing has always been an important craft they have had to learn and master, and a soldiers number one piece of kit in order to maintain standards of uniform was a ‘Housewife’ , also known as; hussif, hussuf, hussy or huswif!

The old-fashioned term ‘housewife’ refers to a portable sewing kit, the term was used in print for the first time in 1749 and was in common use until very recently. However, the term is now banned in modern troops, recognising that the gender specific term is outdated and offensive to women.

The name comes from a time when it was common for mothers, wives and sweethearts in the 18th and 19th centuries to embroider these personalised sewing kits for their menfolk to take to war.

Inside the miniature fabric roll, would contain a thimble, needles, thread, spare buttons and fabric scraps. The ‘Housewife’ was often contained within the holdall and stowed within the man’s haversack.

While women certainly carried and used them, Housewifes are most associated with sailors and soldiers. We know that soldiers on both sides of the conflict brought their own kits in the American Civil War. And in WWI and WWII they were popular items for women’s sewing groups to make to include in care packages. They were standard issue for British soldiers up until after WWII.

Creativity after conflict – mending their lives after war

Many soldiers would turn their hand to ‘fancy work’ whilst recuperating in hospital.

Embroidery was widely used as a form of therapy for British soldiers wounded in war – challenging the gendered construct of it as “women’s work” that was ubiquitous throughout the 19th century. The light bright environment of the hospital bed was the perfect place for them to carry out the meditative, transformative work that was helpful to their rehabilitation.

The stories they stitched into their embroidery was often reflective of pride in their regiment, the fields of battle or messages of love to a sweetheart.

You can read more about convalescing soldier crafts in a previous blog.

Lucknow quilt

We have a very special hand-sewn object in the collection, named the ‘Lucknow Quilt’, yet not actually a bed quilt. The Lucknow Quilt is an example of what are known as “Military Quilts”, which are often a single layer of patchwork with no backing, intended for use as a wall-hanging or tablecloth. In fact, the original notes made at the time of the quilt’s donation in the 1960s describe it as a “patchwork tablecloth”.

It is believed that the Lucknow Quilt was the creation of just one soldier. Unfortunately, we don’t know his name, but we do know that he was batman to a Colonel Birtwhistle during the siege. It was donated to the museum in 1965 by Mrs Brooks, the widow of Brigadier Brooks, a descendant of the soldier, who himself served in the DCLI.

Military quilts were commonly made from the woollen fabric that made up uniforms, as well as blankets and other fabric scraps that may have been to hand. Since our quilt was made under siege conditions, where supplies were extremely limited, it’s likely that the fabric used came from the uniforms of fallen soldiers – red and white from their jackets and blue and grey from the trousers. There are also green pieces of fabric in parts of the pattern which we think is baize from the top of a billiards table that was destroyed during the siege.

The needlework on this particular quilt is very intricate and the stiches are incredibly neat and would have taken a long time for this unknown soldier to complete.