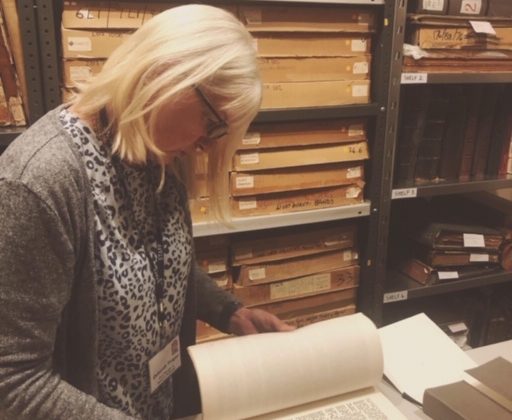

Debs is our research volunteer taking research enquiries from the public and uncovering what she can on their ancestors who fought as a DCLI (Duke of Cornwall’s Light Infantry) soldier in World War One.

Deborah has always been interested in research and was the lead researcher for The Trench Project we were part of in 2018. But since the Corona Virus Pandemic, our military historian Major Hugo White, has had to take a step back, and Deborah has dutifully stepped up to the plate! Deborahs works with Daniel, another volunteer researcher who has a special interest and expertise in the military.

Although Debs is new to military research, she is not new to research in general. She has a keen interest in family research and genealogy and volunteers for the Cornwall OPC – Cornwall Online Parish Clerks website, where she helps people researching their Cornish family ancestry. She transcribes; births, marriages & deaths. Whilst also looking after four Cornish parishes of Fowey, Golant, Advent and Michaelstow helping with any enquiries regarding these parish records.

“It Keeps me pretty busy!”

As a keen ancestral researcher she already had subscriptions to some of the genealogical research sites such as; “Ancestry, Find my Past, The British Newspaper Archive and The Forces War Records “which I’ve started using more now I’m doing more military history”. Deborah explains to me.

“At the museum we have a lot of resources to hand too; the soldier database which has been compiled from records that we hold. From Attestation books which hold basic individual soldier information such as; regimental number, surname & initial, age, occupation… varying from book to book.

It can be difficult as even though a soldier enlisted as DCLI, we may not have the records for him, for example, some of these soldiers may have first enlisted with the DCLI then got moved to different regiments, so the records may have moved with them and he would have been issued a new number, with his new regiment”.

Service Records

Deborah explains that “We don’t actually hold soldier service records here at all, service records pre 1921 especially those for World War One were largely destroyed or damaged during the blitz in the Second World War and only about 30% were salvaged. They have become known as The Burnt Records. This makes tracing a soldier of that period very difficult. About the only intact record of the soldiers and their regimental numbers are the Medal Index Cards and the Service Medal and Award Rolls, thankfully these were stored elsewhere. However, these will only tell you the soldiers name and service numbers and which medals someone was entitled too”

“So, if an enquiry comes through, the first thing I’ll do is check to see if the soldier is on our database. This database is compiled from quite a lot of material which we have here at the museum which covers many years a lot of which is pre-World War One”.

“If I can’t find it as we have some gaps in our records, I then look online. I can often find out which battalion the soldier served with, from the Service Medal and Award Rolls, which are different from the Medal Index Cards.

We also check the solder against our archive to see if we have any objects in the museum or in the archive which relate directly to that soldier. It’s lovely, when, very occasionally we find a photograph of the soldier in our archive”.

Debs tells me about the latest enquiry she is currently working on… “I’ve got an interesting enquiry I’m looking into now, which relates to a WWI medal which was found some years ago in the Bude area of Cornwall. Luckily, our soldier database had been updated with the information that some other medals earned by the same soldier were sold at auction in Truro some years ago”.

“Unfortunately, at the moment, the trail stops there, as there is no information held on the buyer. The finder of the one in Bude would very much like the medal they found to make it back to the family of the WWI soldier, but it might not be possible, as I’ve found out the soldier did not marry and had no direct descendants… but I’m not giving up yet, I’m still working on this one.”

It’s quite a series of detective work Deborah goes onto explain “If it’s an unusual name, even if that’s all I have I can usually find out more by trawling websites and finding some more information. Once I know the Battalion and I know a Service Number, I can usually give them some information on where that Battalion was and what they were doing. For that I refer to Hugo’s book: One and All – which is a very good resource on the Duke of Cornwall’s! Especially if they know the soldier died at a certain date, I can determine, the battalion, and the battle etc, and any actions they were in at that time.”

Deborah also explained that during the national lockdown due to Covid 19, some online facilities have been offered as a free resource, such as The National Archives “You normally would to have to pay £3.50 an item for anything you wanted that has been digitised such as WWI Medal Cards and War Diaries but currently during the present crisis The National Archives have been offering digital downloads free of charge.

War Diaries – A daily account of war

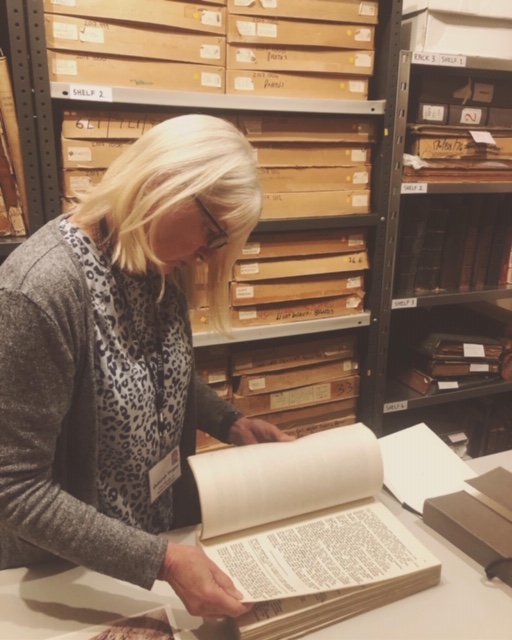

War Diaries are a daily activity log, where each battalion during the war would written down an official account of what happened that day. Bodmin Keep has copies of all WWI DCLI War Diaries. Some war diaries are more detailed than others and some battalions list every single casualty by name. The originals are handwritten, the copies kept at Bodmin Keep are transcribed typed copies.

Each War Diary is different with different contributors documenting the daily activities of the battalion in different ways. Deborah show me an example of an entry by the 1/5th Battalion, which has listed every single soldier with their regimental number, their surname and initial, rank and a description of what happened to them, e.g.; wounded in action, died in action or admitted to hospital. But other battalion war diaries entries, will only record the names of officers who had died and other ranks who perished would simply be recorded as a number.

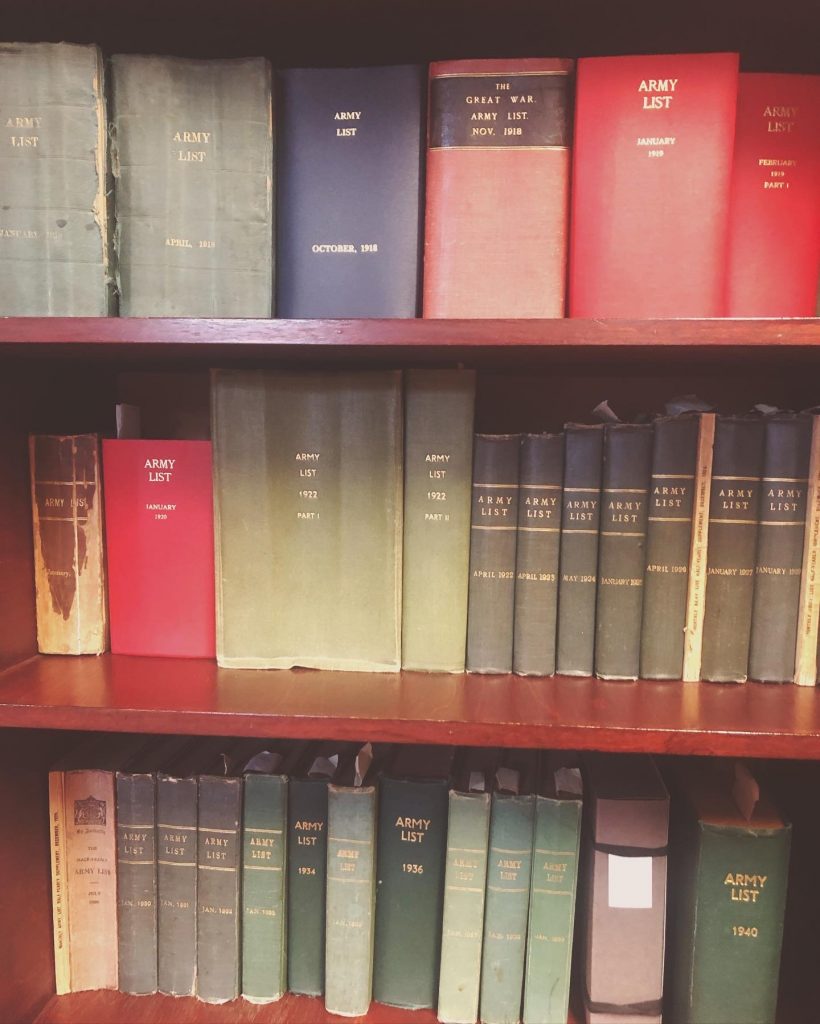

Another avenue for clues is the Army Lists. If they are an officer, you can usually actually track their progress through the ranks by looking through the army lists which we hold at the museum. Army lists record Commissioned Officers in the Army.

Post 1920

Service records for soldiers serving after 1921 are still held by the MOD at the Army Personnel Dept in Glasgow, although we do have some material on soldiers at the museum. I usually refer people to the GOV.UK website which explains the criteria for applying for a copy of records and provides the appropriate forms. https://www.gov.uk/get-copy-military-service-records

When doing this kind of research, it is often remarked that ‘you are only as good as the person who initially recorded the information’. For example in Parish Records you sometimes find the spelling of a name is misspelt by the vicar. And as more people were illiterate back then, these types of mistakes on public records are more commonplace. You often find family surnames spelt in different ways over generations e.g. Symonds, Simmons, Simons, Simones… It’s important to check all options when researching someone. It can be a real piece of detective work.

“And then there’s the common surnames. My maiden name was Jones, which I thought was a really common name, but that was until I started researching the DCLI… where Williams is a particularly common soldier surname!”

“At the turn of the century when fathers and sons often had the same first names the sons were often known locally by their second forename, this can make research difficult. This was evident when we were doing research for the Trench Project and referring to the local Rolls of Honour. It caused a lot of head scratching”. Deb recalls.

Another issue is how sometimes, family stories about the relative over time get changed and altered. Sometimes it will be revealed that in fact their place of death, age of enlistment or where they are buried, was not what they thought or had learned over the years. Stories get passed on through generations and naturally evolve over time. Many people tell me that their ancestor was only 14 or underage when he enlisted for WWI. Sometimes it is true as at the time as no checks were done. However, a lot of these were subsequently discharged when they were discovered lying about their age.

Attestation (sign up records) insights

Looking at the attestation records for WWI, is a revealing insight into the social history of the time, Deb explains “Some of the occupations recorded at the time of Attestation are interesting and a great insight to the times too; farm labourers, carters, conductors, miners, quarryman, teamster (drives a team of horses or draft animals), glass cutter, dining cart attendant, carman, compositor – (arranged letter blocks for printing), tailors, bill poster, pipe and tube drawers (maker of metal piping or tubes ) and even a night soil man (we won’t go into detail on this occupation!)”

“Quite often you can see two or more men enlisting the same day from the same town with the same occupation. I take from this that they probably set off to enlist together as friends. I recently noticed 5 consecutive entries who were all musicians from St Austell.”

A very large number of these have been transcribed onto our Soldier Database and we also have an old pre-computer system of typed out cards. Any museum accessioned items are recorded on the museum artefact database called ‘Modes’.

Recently the museum was contacted by a TV programme research department as they were making a programme tracing any living relatives of fallen unknown soldiers discovered on the battle fields of WWI through his DNA. Hugo was involved with researching the DCLI soldier whose remains had been discovered and was traced back to Bodmin Keep.

This was very poignant but also exciting when we had a visit from Davina McCall and the team from the Ministry of Defence’s Joint casualty and Compassionate Centre (JCCC) along with the living relatives who had been found.

If you would like to us to investigate a DCLI relative of yours, please do get in touch. Just email research@bodminkeep.org with any information you have:

Full name and regimental number (rank, regimental number, surname and initial are punched into the outer edge of their medals). Information on where they were born, date of birth, next of kin, married, descendants, wife’s name, parents name – are all useful when trying to find elusive DCLI ancestors!

We ask a small donation of around £25 for us to carry out any research enquiries which supports the museum and the work we do.