Lance Corporal William John Bonney

Service Number 5436848

1st Battalion Duke of Cornwall’s Light Infantry

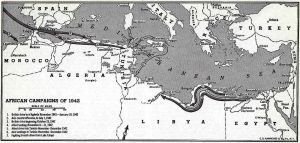

Lance Corporal William John Bonney was captured with the majority of the 1st Battalion Duke of Cornwall’s Light Infantry (DCLI) during and immediately after the battle of Bir el Harmat in the Libyan desert (June 1942). The information used in the following article has been obtained from primary source material held within our Archives at Bodmin Keep. This too includes documentation belonging to William John Oliver, another soldier of the 1st, also captured at Bir el Harmat.

It is often said that the most dangerous period for any Prisoner of War (PoW) is the immediate aftermath of capture. Yet, as William Oliver relates, this was not always the case. Many of those captured from the 1st were held in North Africa for three months and during this time, starvation and disease was a life-threatening reality. Oliver himself states that the Camp Doctor saved his life by admitting him to hospital with a case of suspected diphtheria (presumably starvation cases were not admitted). The additional care and nourishment undoubtedly saved his life. We can therefore imagine that Lance Corporal Bonney’s cheerful assertions that he was ‘A1’ in letters sent home to his family, were probably untrue.

From North Africa, initially both Oliver and Bonney were transferred to PoW camps in Italy. In the case of Oliver – to Camp PG 70, approximately 30 miles due south from Ancona on the east coast. Bonney on the other hand, was sent to Camp PG 148, just outside Verona. Both men were eventually moved to camps in Germany.

What can we learn from Bonney’s letters?

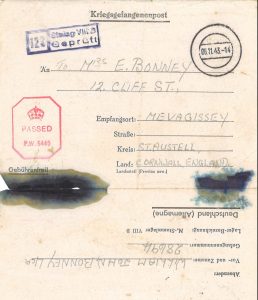

Firstly, it is clear to see from Bonney’s PoW letters, just how valuable such correspondence, often containing news from home would have been. It’s also possible to discern a narrowing of outlook for the prisoner. For example, other than enquiring after family and friends, the main topic of conversation from Bill is regarding clothing and ‘cig’ parcels.

In most cases, Bonney signs off his letters as, ‘Your Loving Brother Bill’. Hence, alluding to the fact that the lady he is writing to, is in fact his sister. Although, it is apparent from ‘Office Form 114 issued by the Regimental Pay Office, Exeter’ that Mrs Melvena Bonney (referred to in his letters as Mel), was actually his sister-in-law. Presumably therefore Edward, mentioned in the letter dated June 26th, 1943 was his Brother. There was obviously a very close bond between Mel and Bonney. Particularly, as there is no evidence of any supplementary correspondence between Bonney and other family members. In addition to Mel and Ed, very few other names crop up. There is Mary however; Bill’s sweetheart, whom he hints at a possible engagement with. Frustratingly, we know very little about the fate of their relationship.

From his letters, we also know that once Bill arrived in Germany, he came to work at a paper factory in Stalag VIII B near Lamsdorf. Interestingly William Oliver also seemed to finish the war working in a German paper factory – although it seems this was over 200 miles west of Bonney’s camp.

William Oliver’s experiences as a PoW are summarised in a page and a half of A4 text, written in June 2004, over 60 years later. Other than stating that the guards were ‘kindly’ and that conditions in Germany were preferable to other previous camps in Italy and North Africa, Oliver recalls little about the day-to-day dreariness and struggle of camp life. There is however a clear sense of thankfulness for his own survival, with acknowledgement and regret that he came through when so many of his comrades did not.

Conversely, William Bonney’s letters are raw from the immediacy of the time. There does not appear the fondness of memory that time sometimes gives to such an experience. Bonney references no friendly guards or walking over a footbridge so a German guard could buy everyone a beer. Only once does Bonney mention what he actually does with his time when he speaks of his work in the paper factory. It might just be that we do not have all the correspondence Bonney sent and we definitely do not have Mel’s responses. However, for all that, the comparison between Oliver and Bonney’s recollections certainly throws into sharp focus the difference between obtaining material from contemporary documents and text that was written over 60 years later.

Written by Andrew Sims, Archivist at Bodmin Keep, May 2021