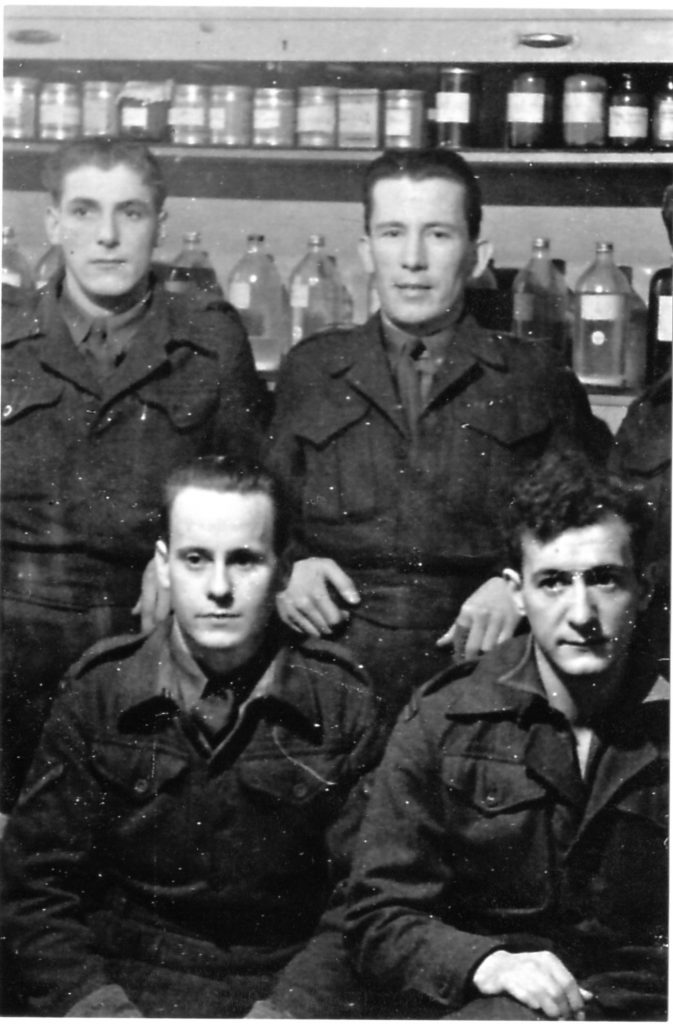

Remembering Matthew O’Connor, by his daughter, Polly Dymock. (Pictured above: Matthew O’Connor, far right)

Matthew Miles O’Connor was born on 20 March 1927. He was the fourth of six children born into extreme poverty, not helped by the fact that his father died when he was 3, leaving his mother to bring up those children (one a new born baby) by herself before the Welfare State.

He was evacuated to Somerset, near Clevedon, and it must have been a vastly different world to the slum streets of Paddington, where he grew up. He was lucky in that his hostess was very kind to him and he soon settled in, getting a paper round and giving his younger brother and only sister pocket money. They were in different billets in the same area and he made sure they were OK.

After his return to London, he went to Cardington in Bedfordshire (by coincidence not far from where I now live) and volunteered to join the Air Force, but as he was still only 16 they fed him, gave him a bed for the night and sent him home the next day.

When Dad was waiting to be called up, he worked in a garage in the Kilburn High Road near a cinema. He saw people like Gracie Fields arrive for publicity for their films, but one day a limo pulled up and John Wayne got out and spoke to Dad – “Hey, son..!” After some discussion it transpired that John Wayne, or his people, had the wrong day!

Dad enlisted in 1945 when he was 18, and after basic training was assigned to the Duke of Cornwall’s Light Infantry. He was very proud of belonging to the Regiment and when his grandsons, Andy, Stuart and Stephen, were smaller we all visited the Museum at Bodmin Keep so that he could show them the history of the Regiment. Andy, his eldest grandson, joined the Army and was in the Royal Signals, serving in Iraq and Afghanistan. Dad loved his grandsons very much, and was very proud of each of the three boys.

My father served in Germany and told me different stories about things he had seen and done in that time.

He drove an ambulance and broke the rules one night by taking a desperately ill little girl to hospital – she was the child of a local man who begged Dad to help. She was suffering from diphtheria and I think it was extremely cold that night. He hoped she survived.

His battalion were guarding the woman who notoriously had lampshades made from the human skin of those incarcerated in the evil concentration camps.

(Ed: Ilse Koch, wife of the commandant of Buchenwald concentration camp, was said to have had prisoners killed in order to collect their tattooed skin).

Dad also worked as a clerk, and was very deeply saddened by the fact that his battalion had to repatriate those liberated from the camps. He said that many were stranded in railway cars in the bitter winter because of the lack of co-operation from local authorities which could have made the task much easier. He believed many of the survivors died in the cold, in the railway cars which had been stalled on the lines.

He told me that some sergeants bought some illegal hooch and one at least died and another was blinded as it was stolen fuel.

There were men in his unit who looked up to new arrivals from their area (Bolton) as “they’d got water closets in their street!”

He married Patricia Turner, known as Trixie, in July 1950 and remained happily so until Trixie died in 2004. He passed away in 2008 and is sadly missed.

Written by Polly Dymock, Matthew’s daughter.

The museum would like to thank Polly for kindly sending us her father’s stories, memories and photographs.

If you would also like to share a story with us to be featured in our newsletter and added to our archives, please get in touch.