Corporal Neville William Hutchinson (Bill)

Service Number 5437332

HQ Company, Signal Platoon, 2nd Battalion Duke of Cornwall’s Light Infantry

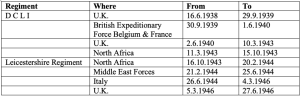

The information contained in this article has been drawn from notes made by Corporal Neville William Hutchinson, although it has been edited to reduce the length. It recalls his first impressions upon enlisting in the Army in 1938. The flavour of early army life is here for all to see but Corporal Hutchinson also served a full part in the Second World War, his Regular Army Certificate of Service shows the following.

Service in three areas of operation, including evacuation at Dunkirk and participation in the hard-fought Italian campaign testify, along with that of his comrades, to the bravery and endurance of the Second World War generation.

Joining up

When I was 17 and for reasons that do not concern us here, I decided to enlist as a soldier. I presented myself at the recruiting office in Worcester. The recruiting sergeant wasted little time on pleasantries and as I had no preferences apart from wanting to get as far as possible from home, acquainted me with the Duke of Cornwall’s Light Infantry (DCLI).

As I was underage, I was only able to sign for a six-month provisional period of service. At the end of which I could, if I wanted, sign up for the full time of seven years with the colours and five on the army reserve. After a caution reminding me of the binding nature of the agreement, I took the oath and the King’s shilling and from that moment I was in the army.

I was given a railway ticket and instructions for my journey. It may seem incredible in these days of extended travel and a shrinking world for me to admit that as the train passed between Dawlish and Teignmouth, I saw the sea for the first time. Upon arrival at Bodmin railway station I was met by a Lance Corporal who led the way the short distance to the main entrance, past the war memorial and into The Keep.

After a meal I stayed for the first night in the recruit’s room, the fief of a bemedaled old soldier who gave new recruits words of wisdom and advice to guide them. The bed was hard but adequate, consisting of three two-foot square horsehair mattresses known as “bisquits” on a metal bed frame, I slept well after my long journey. At daybreak next morning a bugle call outside the window blasted me awake and I heard the call being repeated at various points among the buildings.

My bed was quickly stripped, and I was shown that the bottom half of the frame could be slid on runners underneath the top half and the three mattresses so arranged with one as a seat and two placed upright like a chair back and all covered by the folded blankets into something resembling a fireside chair. An arrangement universal to every barrack room I later came across.

A short time later I heard the noise of pounding feet outside on the path and saw a group tearing up the hill as though their very lives depended on it.

“What are they running for?”, I asked.

“They are not running” replied the old soldier “they are marching, and that’s the pace you will be marching at from now on.”

I began to entertain doubts as to the wisdom of what I’d entered into. 140 paces to the minute was almost a casual stroll by the time I had been in the regiment a few weeks.

Later that first day I was taken to a barrack room named ‘Waterloo’, joining other recruits. When sufficient numbers of us had been assembled we would be formed into a squad to commence our basic training. Until that time life seemed to consist of endless roll calls and counting files in the ranks and constant references to notebooks by our NCO instructors. It soon became clear that all this was part of service life. The senior ranks would always want to know where we were and what we were doing, as I later found out, everyone no matter what is rank, was always at all times answerable to the ranks above.

Everyone not an NCO was dressed in a curiously shapeless baggy canvas suit, buttoned up to the neck and with five brightly polished buttons down the front. The jacket had two patch pockets, one on each side. Trouser bottoms flapped around ankles and in colour of every shade from a dark red sandstone to a washed-out biscuit. This working dress was known as canvas and was the recognised wear of other ranks in the barracks saving wear and tear of the uniform proper. The variation in colour was caused by constant washing and laundering, during which the original sandstone dye became washed out of the material.

Clothing and equipment were issued to us from the quartermaster stores, two of everything from top to toe. We had been given our army number, and this was stencilled or punched on every item issued to us. Even our boots had our number stamped on them at the ankles.

When we started our basic training, my squad had four NCO instructors. In order of seniority, they were Sergeant Atwood, under him was Lance Sergeant Hall, the quartet was completed by two Lance Corporals, Smith, and Emerys “Jack” Davies. Sergeant Atwood left Bodmin to re-join the second battalion as CSM of ‘A’ company. His replacement as our chief instructor was Serjeant “Dickie” Best, of stocky build and swarthy bulldog looks, strict and yet fatherly to us recruits. Later as CSM of, I think ‘C’ company in the second battalion he was killed in the fighting in Tunisia.

On the Barrack Square we were taught the basics of foot drill whilst earnestly trying to avoid giving the instructors apoplectic fits. Learning to adjust our stride to the regulation 30 inches so that everyone from the shortest to the tallest in the squad covered the same amount of ground in a given number of steps. It was remarkable how quickly we became a cohesive group and took pride in being so. Saluting was high on the list of things for us to learn and pay parade was a test of our efficiency in this respect. I remember the drill; when your name was called, march in as smart as possible to the officer’s desk, halt, salute, take one pace forward, take your pay in the right hand, transfer it to the left, take one pace backward, salute, right turn, pause, and march away.

A sergeant from the Education Corps would give in-depth talks on regimental and military history. Having only ever attended a village school hearing him was the first time I had heard anyone talk in depth on a subject and they were a delight to me. I’ve forgotten his name, but I’m sure he opened my mind a little more than hitherto.

My squad gradually became more skilled at soldiering and thoughts of moving on to join the second battalion began to enter into our conversation. We said goodbye to the barracks, not with too much regret, and marched from the square, through the arch of the Keep, past the war memorial, and down to the station to begin our journey to the regiment, then stationed at Alma barracks, Blackdown near Aldershot.

I started regimental life as a private in ‘B’ company. In the autumn of 1938, the battalion moved to Moore barracks, Shorncliffe, near Folkestone in Kent, the very place where Sir John Moore began to train the first Light Division during the Peninsular wars. The Barracks were rather old-fashioned but nicely situated on the clifftop overlooking the sea. The Channel’s changing moods during our first winter there were a source of some interest. Eventually, someone, somewhere, decided I was to become a signaller. Once again, I packed my kit bag for another move. This time to HQ company, the home of all the specialist platoons. I trained to become a signaller with some success under the signals officer Lt Vawdrey who was later to become another casualty of war while serving with the fifth battalion in Europe.

During the time of my signals training a draft was sent to the first battalion in India with it went most of the squad I trained with at Bodmin*. I know of only three of us who survived the war, though there must be others who outlive those battles. I often wonder what became of them all.

14th March 1995.

* It has been frequently said – the part fate plays in war, much of the 1st Battalion was destroyed as a Battalion in its first battle in North Africa.

Written by Andrew Sims, Archivist at Bodmin Keep, June 2021