The high levels of injury caused to arms and legs, from shells, bullets, and frost bite during the First World War, caused the need for increased development of artificial limbs.

Previously artificial limbs were made to order for the very wealthy. One of the lead manufacturers of artificial limbs in the First World War was the Desoutter Company. Founded by the Desoutter brothers, after one brother Marcel, an aviator, lost his leg in a crash in 1913. The wooden leg he had was uncomfortable, so his brother Charles made him a metal leg which was lighter, more comfortable, and much more practical. Made from the new lightweight alloy of aluminium, duralumin, which was only discovered in 1910, this allowed Marcel to fly again. From here the company grew, going on to make many prosthetic limbs for veterans of the First World War.

Queen Mary Convalescent Auxiliary Hospital

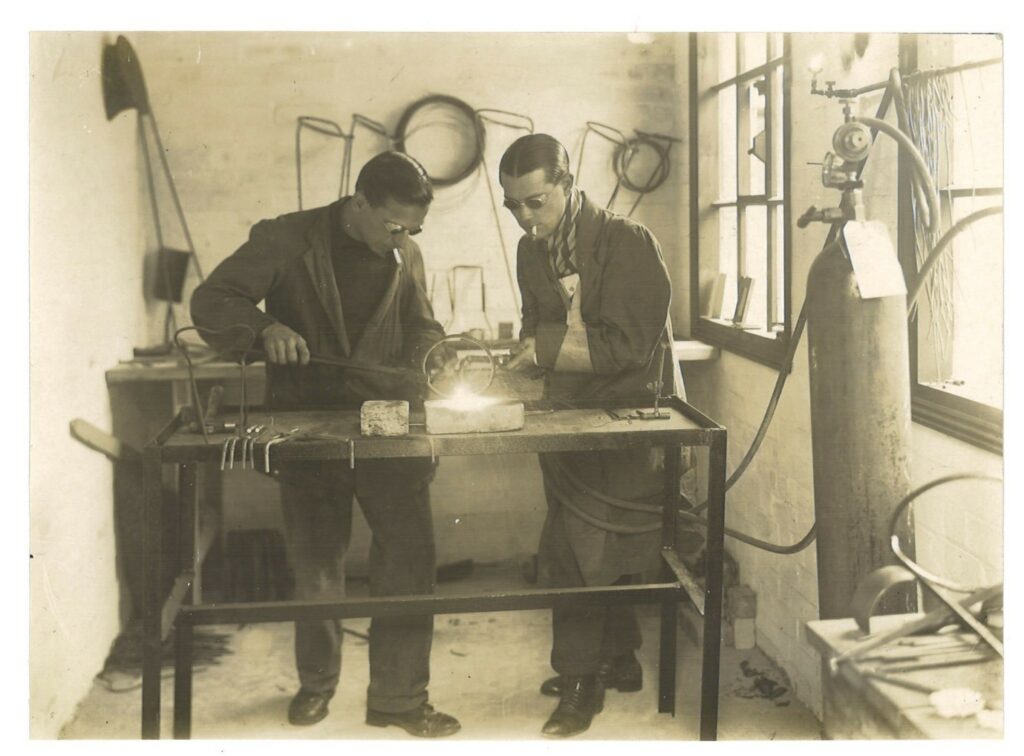

Many of those working on making these artificial limbs were injured ex-servicemen themselves, giving them a new skill and trade on their road to recovery. In a specialist wing of St Mary’s Hospital in Roehampton, previously named ‘Queen Mary Convalescent Auxiliary Hospital’, artificial limbs were fitted to each soldier as the workshops were onsite. Having been established during the First World War, the hospital is still world famous for its amputation rehabilitation.

The prosthetic arm depicted here was made at St Mary’s with the words ‘Hugh Steeper. Ltd Roehampton House London SW15’ stamped into the leather upper arm. This arm belonged to Private Harry Owen Williams who was a stretcher bearer. It is thought that he was posted out with the Duke of Cornwall’s Light Infantry at some point between August-September 1915 after enlisting in May that year. It was in Ypres that not only he lost his arm but also the rest of his party of stretcher bearers. He was discharged 19th December 1918. However, this could not have been his first prosthetic upon discharge from the army as Hugh Steeper Ltd was founded in 1921 and not based in Roehampton until 1923. The postal address to which the prosthetic was sent to is also different to that recorded as his home address on his discharge from the Army.

Most prosthetics of this period had multiple attachments to allow the user to perform every task an able-bodied person could.

We have our new Fit to Fight exhibition in the museum, where you can visit and see the prosthetic arm.