Life as a Soldier at Bodmin Barracks.

Bodmin Keep was built in 1859 as a headquarters for the Royal Cornwall Militia, the volunteer force of the period.

It wasn’t until 30 years later in 1881 that the site became the headquarters of the DCLI, and the Keep became the Officers’ and Administrative HQ and Quartermaster’s stores, where uniform, mobilisation equipment & weapons were stored.

A New Recruit

When a new recruit came through the imposing front gates of the Barracks, the first job would have been to get his army kit.

On the first floor of The Keep there was a long wooden counter where kit was laid out. The new recruit would first be issued a heavy canvas kit bag and then he’d fill it with his army kit as issued; a great coat, pair of boats, 2 sets of battle dress (best and second best) which wouldn’t have fitted very well, underwear, and a ‘House Wife‘ (pronounced Hus’if) which was a maintenance kit in a roll which contained; darning wool, sewing kit, needles, boot cleaning kit, razor, soap, comb and toothbrush.

The recruit would arrive in their civilian clothes then change into the khaki denims he would have been issued with. These were the everyday working clothes that soldiers wore with heavy army boots and a cap. This arrival ritual of kit dispensing and the type of kit issued varied very little from 1881 until the depot closed down in 1968.

Once he had his kit, the recruit would be instructed to go and have his medical examination at the barracks hospital. Usually a barracks medical area was just a hut but at Bodmin the medical unit was a big hospital complete with a mortuary.

After the medical examination the recruit was allocated his barrack room and bed space. In those days each barrack block accommodated around 28 men. It had 4 barrack rooms; 2 on each side with granite staircase which ran between the two sides of the residential accommodation.

Each soldier had a concertina bed, with three ‘biscuit’ mattresses which folded up into a chair during the day. Behind each bed were 3 pegs to hang your webbing up on and on top of that was a shelf for your big pack, small pack and helmet. A soldier’s box for private possessions would have been kept under his bed and each bed also had wooden block next to it, to prop rifles against at night.

National Service

The British post-war government realised the need for a larger armed forces, so the National Service Act 1948 was brought about. It required all healthy young men aged 17 – 21 to serve an 18 month National Service in the army. It became a rite of passage; young men would arrive at Bodmin barracks often by train, entering as young boys and leave after 12 weeks training as trained soldiers posted to exotic places like Korea, Malaya or the West Indies.

The Daily Drill

Very few people had watches during this time; they were rare and expensive, so your day was governed by the bugle which sounded every 30 minutes with a different call. Reveille would sound at 6am to start the day and the soldier would make his bed, fold away his blankets and lay out his kit ready for daily inspection.

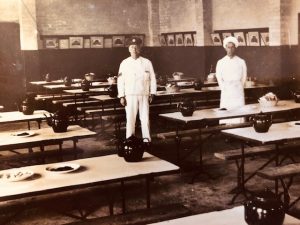

Next would be breakfast where every soldier would take his pint mug, knife, fork and spoon off to the Mess Hall. Before 1920 food was eaten in the Barracks Room – the Mess Orderly would go and queue up at the Cookhouse door and bring back the meals for the soldiers in the Barracks Room. After 1920 dining rooms were introduced so all soldiers could eat their meals in a dedicated Mess Hall.

Breakfast was always a good meal comprised of porridge, full English, a pint of tea and as much bread, butter and marmalade as you could eat. The recruits were growing young men and always hungry!

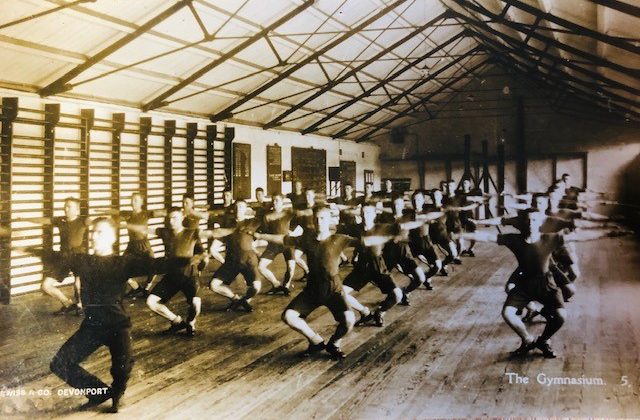

After breakfast it would be inspection and ‘fall in’ for parade, drill, physical training (PT) & weapons training. Drills were, and still are, a big part of the training, creating a strong soldier ethos of obeying command instantly, breeding team spirit and bringing out pride in the soldier.

Most depot barracks had a swimming pool where every recruit was taught to swim, the pool also doubled up as an emergency water supply.

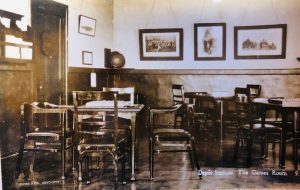

Down Time

New recruits were not allowed to leave the barracks for the first 6 weeks, after which they were permitted to venture into the town. But if you heard the T‘too – or ‘tap two‘ bugle call; you had to drink up as it was your half an hour call to turn the taps off, get out of the pubs and back to the barracks!

Cleaning

Immaculate presentation required a lot of maintenance and the daily inspections and parade made soldiers very proud of their turn out. Often recruits would get their ill-fitting battle dress taken in at the tailors in town, so it would fit them better, and boots were smoothed out with a hot spoon, and hours of spit and polish with a duster to get the perfect shine. Major Hugo White tells me that the way to get a mirror shine was to use methylated spirit as well as a good dose of spit!

They would clean their webbing using ‘Blanko’, some water and a scrubbing brush. Each soldier would have paid for his cleaning products out of his weekly wages.

Money

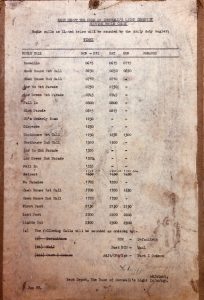

A National Service Soldier was paid £1 a week and a Regular Solider 28 shillings a week (in the late 1940’s). Every Friday afternoon it was ‘Paper Aid’, where the Paying Out Serjeant would have a list of every soldier’s name and what he was to be paid against it. The money was withdrawn from the local bank, counted out and then escorted back to the depot. When the Paying Out Serjeant paid each soldier his allowance, 2 randomly appointed soldiers would oversee as witnesses.

All the soldiers needs were catered for at the ‘NAAFI’ – the Navel Army Air Force Institute, where they could get ‘Char and wads‘ for tuppence (which means tea and buns).