Military Museums for Mental Wellbeing

Wellbeing seems to be the buzzword on everybody’s lips at the moment, especially with the ongoing COVID-19 crisis. But surely there are more engaging ways to feel well than putting on some whale sounds and staring into space for ten minutes?

I’m convinced that military museums, like Bodmin Keep, have collections and stories which can genuinely support people’s mental health and wellbeing.

When I have posed this concept to others, I have received more than a few raised eyebrows. Aren’t military museums all about horribly depressing periods of history – war, conflict, death, suffering?

Think of something terrible and you’re bound to find it represented in a military museum? Well, yes. And that is exactly why they can help us feel better!

Military museums remind us that we will all die.

Acknowledging our own mortality can encourage us to value and enjoy the life we have, while we have it.

When a visitor wanders around Bodmin Keep’s galleries, or trawls through our online resources, they are confronted with an armoury full of weapons, a helmet pierced by a bullet, letters from soldiers who witnessed the death of friends, the remnants of explosives, and medals dedicated to fallen troops. The museum is immersed in stories of death. On the surface, this is fairly grim, but it has been proposed by psychologists and wellbeing professionals that by sitting with the knowledge that death is coming for us all, we can be reminded to pursue the life that we want before we go.

Of course, graphic confrontations with death can be deeply upsetting for people, especially those who are in the midst of grief or experiencing a trauma of their own, so it is worth acknowledging that only those, who feel like they can do so comfortably, take a deep dive into this.

However, there are benefits to thinking and discussing death in your everyday life. Being conscious that our time on earth is finite can motivate us to live in the present and do things now rather than later.

Furthermore, thinking about death in our daily lives has been shown in some studies to encourage compassion and empathy towards others. So that Lee-Enfield rifle mounted on the wall is a reminder to not sweat the small stuff, do what makes us happy, let go of old grudges, and be nice to your mother.

Military museums unflinchingly show us real hardship and encourage us to be grateful for the comforts we take for granted.

Military museums tell stories of incredibly frightening periods of history, during which people suffered through hardships that many of us today will never know. This can help us to realise the privileges that we take for granted and practice gratitude, one of the tenets of mindfulness: a widely followed wellbeing practice.

Take Bodmin Keep’s ‘Lucknow Quilt’, a counterpane stitched together from the uniforms of dead soldiers by someone enduring the siege of Lucknow, India in 1857. 3000 people, including 32nd Regiment of Foot soldiers, women, children, and civilians, were trapped inside the Residency in appalling conditions for nearly 6 months.

The diary of Lady Julia Inglis offers us some insight into the horrors that were faced inside: disease, infant fatalities, and starvation. To think that someone had the strength and patience to complete this delicate stitching whilst living through such trauma is astounding. I try to keep this in mind whenever I am tempted to yell expletives because my live-streamed yoga class has started buffering.

Of course, many people today are anxious about their health, work, and relationships like never before. Not to mention the people, who on top of all the lockdown uncertainty, also are enduring domestic violence, poverty, or homelessness. I try to stay conscious of this, which keeps me aware of and grateful for my own privilege.

We all have our struggles, of course, and we shouldn’t ignore or deny them. But it massively helps me to keep some perspective. Hearing the stories of others, past and present, who bear such unimaginable hardships, can teach us how to endure our own, and keep things in proportion.

Military museums can be safe and sensitive places to encounter these stories.

Military museums help us to create connections and feel less alone during tough times.

Whilst keeping an element of perspective, it can be comforting to know that grief, fear and uncertainty are universal. Military museums hold many personal stories of individuals who have been through challenging times. Engaging with their collections can be a valuable way for people to find connection, and perhaps feel less alone.

Take our miniature chess set, donated by Private Patrick Linehan. Patrick served in the DCLI during WW2 and was held as a Prisoner of War (PoW) in Munich from 1944-1946.

This chess set was given to him by a fellow PoW whilst he was imprisoned. For me, this tiny board game represents resilience, sticking out a horrible experience and finding moments of joy where you can.

Whilst I’m stuck at home desperately trying to amuse myself with the umpteenth game of scrabble, I think of Patrick and what he went through. His story inspires me to make the best of the situation and just keep on keeping on. We’ll be out of this soon enough.

Military Museums show us what real sacrifice is and inspire us to be altruistic.

Bodmin Keep, and many other regimental or army museums, are built around a central narrative: people risking and sacrificing their lives to protect others. Whether or not you agree with war, or the decisions which the government or military leaders have made, the bravery and selflessness which individual people have demonstrated during times of conflict is undeniably moving.

Whilst I’m not suggesting that we should all start putting ourselves in mortal danger to show our friends we appreciate them, perhaps stories of the actions of soldiers and other service personnel can prompt us all to be a little more generous.

Wellbeing experts repeatedly tell us that doing kind things for others can boost our own mood; ‘Give’ is included as one of the Five Ways to Wellbeing.

Right now there are plenty of people who are vulnerable and could use some assistance if you have any time or money to spare. Perhaps join your neighbourhood’s Mutual Aid group or offer to support a local business which is struggling under lockdown? There has never been a better excuse to order a takeaway from the chippy round the corner.

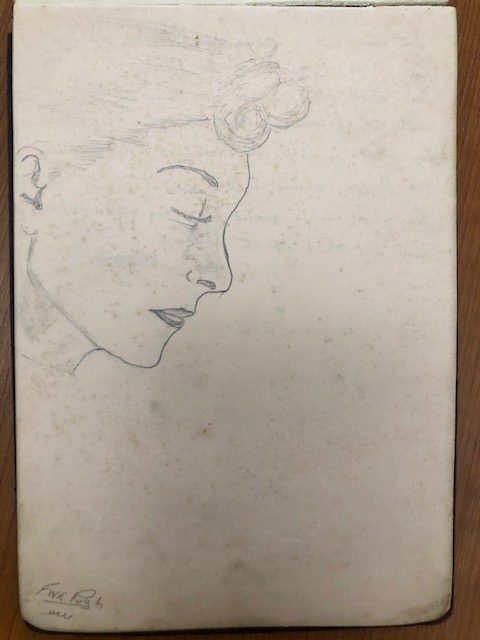

In a similar vein, military museums can inspire us to express gratitude towards the people who do so much for us in everyday life. In Bodmin Keep’s archive, we have an album belonging to nurse Olive Barnicoat, who worked in Bodmin’s St Lawrence’s Hospital, as part of the WW2 Emergency Medical Service.

Inside the album are affectionate messages, poems, and drawings from her patients expressing their thanks to Olive and their appreciation for all the good work she did. It is an intimate, heart-warming thing to read and shows us that even the smallest gestures of gratitude can have an impact. A valuable lesson for these times.

By, Sarah Waite, Trainee Curator at Bodmin Keep