Over seventy-six years ago, on 15 April 1945, British forces, including the 5th battalion of the DCLI, liberated the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp. This blog is about my experience of uncovering two British official (Crown Copyright), photographs captured inside Bergen-Belsen, within the archives of Bodmin Keep.

A Brief History of the Camp

Bergen-Belsen was located in what is today, Lower Saxony in northern Germany, southwest of the town of Bergen near Celle. The camp was initially established in 1940 as a prisoner of war camp, but from 1943, Jewish civilians with foreign passports were starting to be held there as ‘leverage’ in possible exchanges for Germans interned in Allied countries or for money. It later became a concentration camp and was used as a collection centre for survivors of the death marches. The camp then became exceptionally overcrowded and conditions were allowed to deteriorate further in the last months of the war, causing many more deaths. Anne Frank and her sister Margot died at the camp, reportedly of Typhus, sometime between February and March 1945.

Tragically, upon liberation on 15 April 1945, the British discovered approximately 60,000 prisoners inside Bergen-Belsen, most of whom were seriously ill.

My Photographic Experience

As a postgraduate of Documentary Photography, with a specialist interest in still photography from the Second World War, Holocaust atrocity photography is not a new area of research for me. Over the years, I have written a number of essays on the subject and spent a significant amount of time reflecting on both perpetrator and Allied liberator photography. It goes without saying that spending this amount of time with such sensitive and harrowing material, often depicting incomprehensible levels of human suffering, has taken its toll on me.

Why then, was my recent experience of discovering two 8 x 8cm British Official photographs taken inside Bergen-Belsen concentration camp, at Bodmin Keep, so uniquely hard-hitting?

Collection Discovery

Andrew, our archivist, recently discovered a box of research containing, amongst other items, a folder simply titled ‘Joseph Kramer’. Kramer, also commonly referred to as the ‘Beast of Belsen’, was the former Commandant of Auschwitz-Birkenau from 8th May 1944 to 25th November 1944, and of the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp from December 1944 to its liberation, on April 15, 1945.

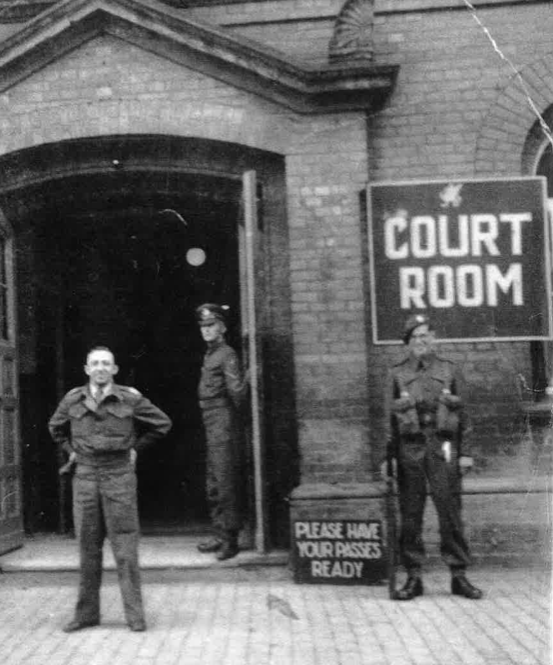

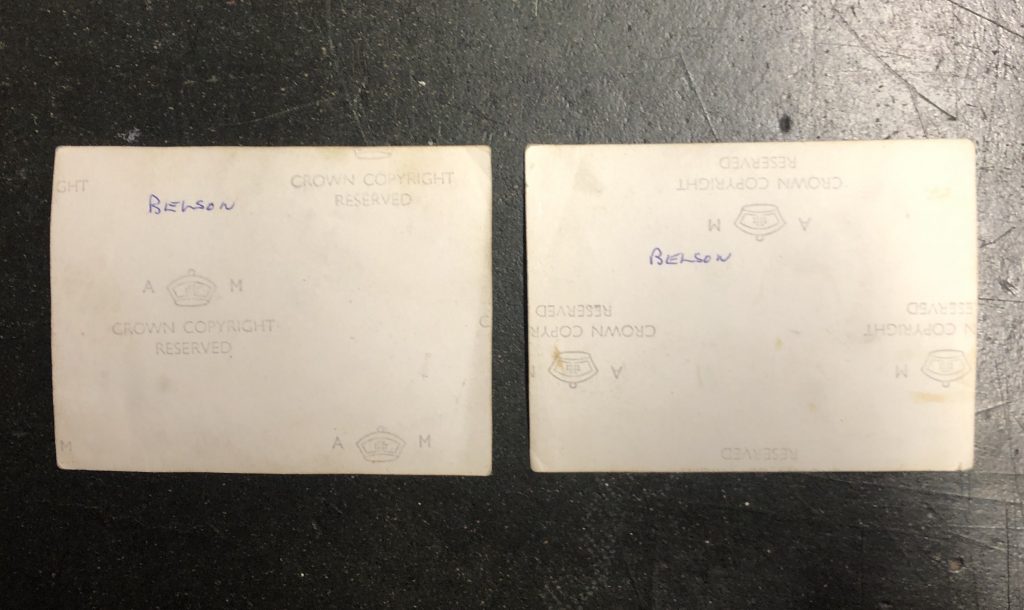

Unsure of what to expect, I flicked through this folder which mostly contained documents, the occasional photograph (see example above) and some printed research relating to the involvement of the 5th battalion of the Duke of Cornwall’s Light Infantry (DCLI) in the Belsen war trials during the autumn of 1945. Towards the back of the folder, there was a plastic wallet containing an ordinary white envelope. Inside was a pair of small photographs; two original, British Official liberator images captured inside Bergen-Belsen concentration camp (see below). Without going into any more detail, the scenes depicted in these two images were extremely distressing and difficult to look at. In fact, initially, I struggled to hold the two photographs in my hand.

On reflection, I think the root of this experience did not lie in the photographic content alone; although truly horrific, the subject matter was not unique to other Holocaust photography I have witnessed in the past. I believe that my heightened reaction can instead be explained by photo-theorist, Susan Sontag’s idea that ‘A picture is always seen in some setting’. By this, I mean that how, where and why I was looking at the two photographs had an extraordinary impact on my interpretation of them.

In the tangibility and physicality of the photographic prints, I found there to be a connection to the subject matter, that I have never quite experienced before. For a moment, when holding each of the two photographs between my fingertips, I felt as though I was staring death in the face. This sense of reality and attachment was only reinforced by the minuteness of the two photographs and the need to look closer for detail.

To justify this, it is useful to compare the way in which the majority of us typically interact with similar subject matter in the 21st century; both digitally and on a screen. Our gaze can often be somewhat ‘tempered’ by the screen as it can serve as a physical barrier and a form of convenient separation between the subject and viewer. In other words, the screen provides a level of emotional detachment not available in a physical print. Perhaps, this impression of distance is also rooted in a sense of comfort, knowing that we, as a viewer, are not the first person to be seeing these photographs. Not only have they been carefully curated, and arranged on screen, but we know viewing them in this way is a shared experience .

Another aspect of my experience of these two photographs, relates to my lack of ‘mental preparedness’ as I simply wasn’t expecting what I uncovered. Although, virtually impossible for anyone to fully ‘prepare’ themselves for such graphic depictions of incomprehensible brutality and atrocity, when confronted with digital Holocaust imagery, it would be very unusual for such material to have emerged as a total surprise. To a certain extent, whether it be through a conscious choice or conducting a related search, the viewer would almost certainly have had an opportunity to subconsciously prepare. This could be equally applicable to atrocity imagery on display in a museum or gallery space. Here, the material is displayed in a space that almost compels a shift in mindset upon entering. This perhaps in turn, moderates our reaction.

In terms of how we present atrocity imagery in a museum, the model of a ‘moderated experience’ is not necessarily a negative thing when we consider how we want audiences to interact with sensitive material. Reflecting on my own experience, I still have the following question: Do we need to see unfiltered atrocity in order to understand the history of the holocaust? Similarly, Susan Sontag asks:

What is the point of exhibiting these pictures? To awaken indignation? To make us feel ‘bad’; that is, to appal and sadden? To help us mourn? Is looking at such pictures really necessary, given that these horrors lie in a past remote enough to be beyond punishment? Are we better for seeing these images? Do they actually teach us anything?

I’m not so sure.

Written by Charlotte Marchant, Second World War and Holocaust Digital Intern.

‘Supported by our Second World War and Holocaust Partnership with Imperial War Museums, funded by the National Lottery Heritage Fund’