During the First World War 306 soldiers of the British and Commonwealth Army were shot at dawn by firing squad for desertion or cowardice. These men brought shame on their country and would be held in the highest disregard to discourage anyone else from doing the same.

Thirty five days into war, Private Thomas Highgate, became the first British soldier to be executed for desertion. Unable to bear the carnage at the Battle of Mons, he had fled to hide in a barn. Undefended at his Court Marshall he was executed at the age of 17 on 8th September 1914. The last two soldiers executed were Pte Louis Harris and Pte Ernest Jackson on 7th November 1918.

For most of the troops of the First World War, the daily trauma of witnessing the horrors of war, day after day, watching your friends and comrades get blown up and whole battalions obliterated took its toll. The few confused, terrified men who shirked their responsibility to flee their post, soon learned that there was no way out of the horror – if they ran from German guns, they would be shot by British ones.

Many of the soldiers who were executed for desertion were teenagers, and there were claims that the executions exposed class issues among the ranks. There is an example of when an Officer was found guilty of deserting his post he was not sentenced to death on grounds of ‘technicalities’ whilst a young Private found guilty of the same, was shot at dawn by firing squad. For the duration of the WWI, 15 officers sentenced to death received a Royal Pardon yet in the summer of 1916, all officers of the rank of captain and above were given an order that all cases of cowardice should be punished by death and that a medical excuse should not be tolerated. However, this was not the case if officers were found to be suffering from ‘neurasthenia’

(Oxford English Dictionary: Neurasthenia – an ill-defined medical condition characterized by lassitude, fatigue, headache, and irritability, associated chiefly with emotional disturbance)

“The predicament that confronted many of these condemned men was quite pathetic. Often in poor physical health, these ill-educated, inarticulate individuals were frequently exhausted from the strains of constant horrific trench warfare which drained their resolve – and ultimately their lifeblood. “Julian Putkowski, Shot at Dawn.

During the First World War, the execution of soldiers was controversial and in total 306 men mostly volunteer soldiers were executed, the majority for desertion and cowardice. By 1930 Parliament had introduced legislation banning the death sentence for the crimes for which the 306 men were shot.

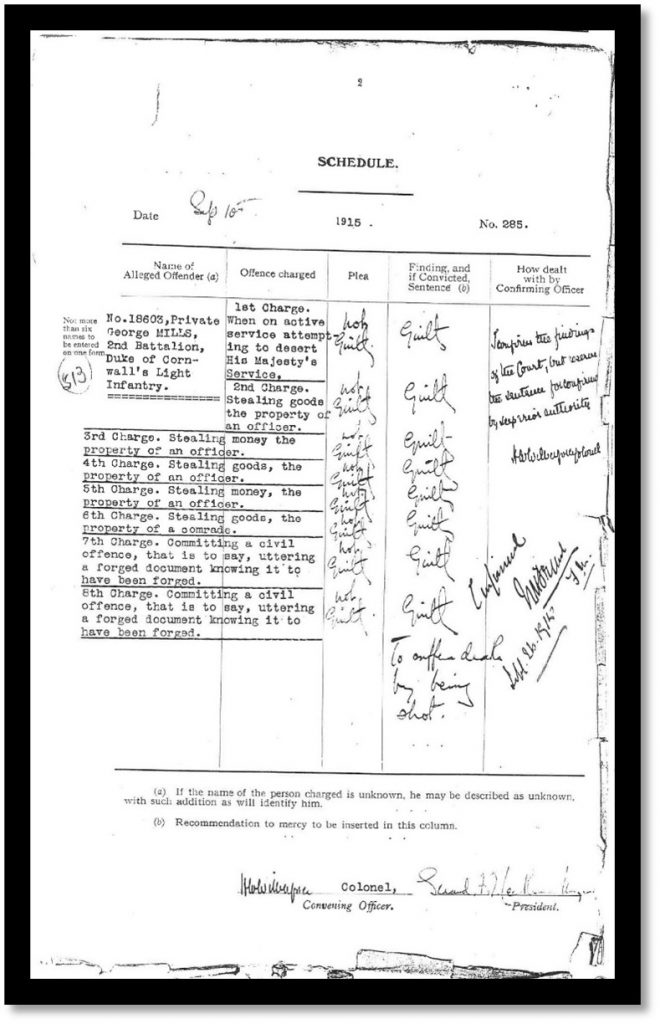

Of the 306 Soldier’s shot at dawn only one was from the DCLI, he was Private George Mills. He was Court Marshalled for the offence of desertion along with 7 other offences for theft, you can read more about him below.

A list of all the British and Commonwealth men Shot at Dawn are listed here:

In an essay for Chloe Dewe Mathew’s book, Shot at dawn, the historian Hew Strachan defines many of the victims as “men who were not yet legally adult, because they had enlisted underage; men who were suffering from what was then called shell shock; men who genuinely became lost in the confusion of battle; men whose courts martial were in the hands of officers who lacked legal training and so were not properly conducted”

Shell shock

Shell shock, now defined as Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), was first recognised in print by Dr Charles Myers of the British Psychological Society in 1915. It seems obvious to us now, that these soldiers were undoubtedly suffering from shell shock after being exposed to the unimaginable horror of war, yet with no formal medical examination or representation, the soldier was made an example of and tried as a coward.

By the end of the war the army had dealt with more than 80,000 cases, and Shell Shock was widely recognised as a severe psychiatric breakdown due to psychological trauma. The condition would make soldiers behave erratically on a spectrum of hysteria to catatonic.

Those in the firing line would also have suffered too, having to kill your own friends and comrades would have caused lasting emotional pain.

It is distressing that these young men who signed up to fight for their country and who were sent out to the trenches and exposed to unimaginable horror, should be executed by their own men because of mental breakdown and seems brutally unjust.

The military death penalty was outlawed in 1930, and in November 2006 the Armed Forces Act granted a mass pardon to all the men who were executed in World war One.

The law removes the stain of dishonour with regards to the execution on war records, but it does not cancel out the sentences. Defence Secretary Browne said: “I believe it is better to acknowledge that injustices were clearly done in some cases – even if we can’t say which – and to acknowledge that all these men were victims of war. I hope that pardoning these men will finally remove the stigma with which their families have lived for years”.

We now understand so much more about psychiatric breakdown, and although there is always more to learn, military and societal attitudes are aligned and the modern open conversation around mental health works to remove the stigma and leans towards a better understanding and treatment of military stress caused by trauma and combat.

Private George Mills

Private 18606 2nd Battalion DCLI

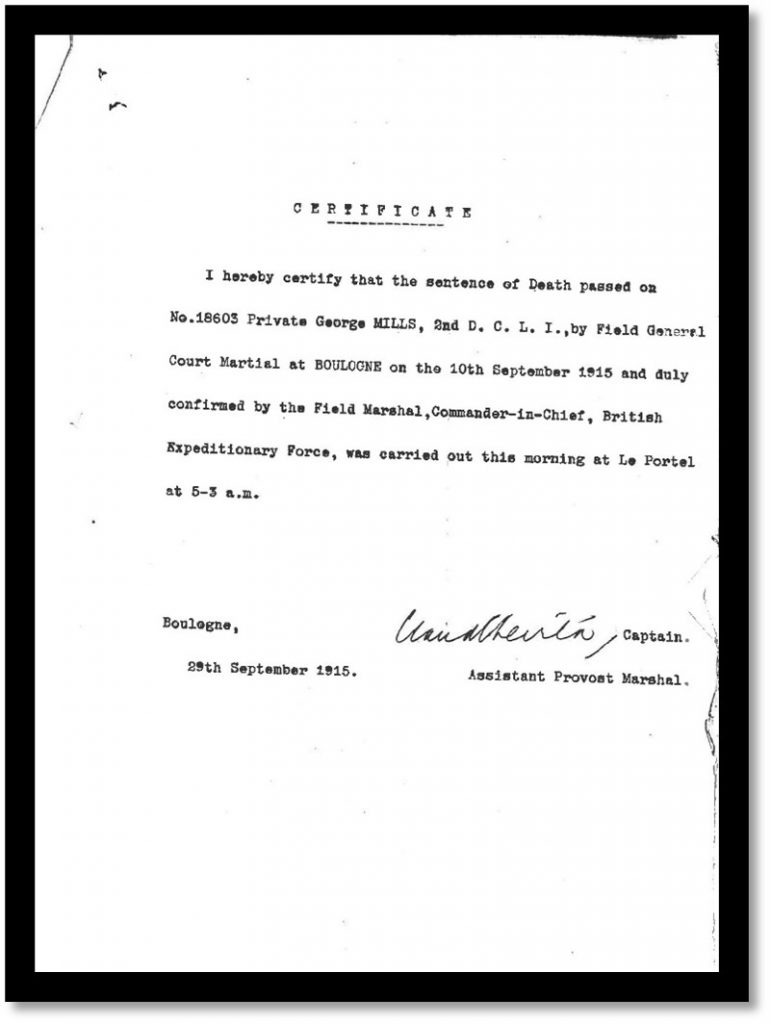

Shot at dawn on 29th September 1915, Boulogne

George Mills, the son of Mrs Pilling of 142 Mortlake Road, was born in East London in 1894. George volunteered for enlistment into the Duke of Cornwall’s Light Infantry on the 24th February 1915. Little is known of his background except that he was born in the East End of London in 1894, and is alleged (but not officially recorded) to have had a police record at the time of his enlistment.

Within a matter of a couple of weeks, on the 15th of March 1915 he crossed to France in a troopship, and reported to the 2nd Battalion DCLI later the same day. The date indicates that he could not have completed more than a fortnight’s training, however the recruit training programme of the time was designed to last for six months. This period was occasionally shortened when the manpower demand on the western front was critical. It was, however, unprecedented for this to occur.

His arrival coincided with the 2nd Battalion which was resting out of the line in billets at the Rue de Lettre about two miles south of Erquingham near Armentieres. He was initially employed as a company orderly and later as the soldier-servant of Lieutenant Evelyn Mulock. When the Battalion went up into the line again, Mills was, for some reason, left behind in billets with the rear details.

On 31st July 1915, he stole money, documents and general property belonging to Lieutenant Mulock, 2nd Lieutenant Martin and Private Lucas. Then, dressing himself in officer’s uniform, he went to Boulogne to enjoy his stolen goods. He was quickly arrested.

A field general court Martial was held at Boulogne on 10th September 1915. Mills conducted his own defence; it is not recorded whether he was accorded his legal right to be represented by a defending officer, or whether he refused to exercise that right. In his defence he stated: “The other officers’ servants were always drinking and wanting to fight one another… The other servants were down on me because I did not drink. I dressed as an officer so as not to be stopped by the sentry of my regiment… I intended to go home for a few days and come back again.” He was shot at 5:03 a.m by a firing squad on 29th September 1915.

George Mills was one of hundreds of British army and commonwealth soldiers executed after courts martial for desertion and other capital offences during World War One. They received no medal, are never mentioned in memorial services and their families got no pension. Of the +200,000 men who had a court martial during the First World War, 20,000 were found guilty of offences carrying the death penalty. In total 306 British and Commonwealth soldiers were executed during World War One. George Mills was the only DCLI soldier to receive the death penalty.

George was buried in Boulogne, among other soldiers. His record says: 18603 Private George Mills, 2nd Bn. Duke of Cornwall’s Light Infantry, executed for desertion 29th September 1915, aged 21. Plot VIII. B. 81. Son of Mrs Pilling, of 142, Mortlake road Prince Regents Lane, Custom House, London.

Sources, further reading:

Shot at Dawn by Julian Putkowski and Julian Sykes (Pen and Sword, 1998)

Shot at dawn – Chloe Dewe Mathews (Ivory Press 2014)